08 September 2020

The Invasion of Red Army in Tbilisi in February 1921

Soviet Russia represented the occupation of 1921 as an internal rebellion and the Bolsheviks as the supporters of rebels. In March of the same year, different types of propaganda began and continued for several years.The 11th Red Army of Bolsheviks was renamed as the “Liberator Army” and the full-scale campaign about the benefits of the communist system started in the newspapers. Also, there was a huge share of black PR against the previous government and politicians. There were lots of reports how Noe Zhordania refused to open the stocks and instead of giving food to the poor, the stocks went bad – the Communist historiography repeated this fact for 70 years. The Bolsheviks demonstratively opened the stocks and gave the unblemished food to the people and carried out many similar activities.

Similar processes were evident in the other Soviet republics. For instance, the Soviet regime actively demonized the Workers’ Social-Democratic Party of Ukraine. Soviet propaganda represented it as a bourgeois, nationalist party and declared its members as the enemies of the people. The same was true for the Armenian Dashnaks – the representatives of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation who ruled the First Republic of Armenia. In 1937, many people, who were accused of collaborating with these parties, became the victims of Stalin’s repressions.

Regardless of active propaganda, the above-mentioned methods did not turn out to be successful in Georgia. The Bolsheviks and Communist Party did not gain popularity through blandishment. This is proved by the meeting between the local workers and the most influential Caucasian Bolshevik, Joseph Jughashvili at Nadzaladevi Thatre, in June 1921. Stalin was in the Northern Caucasus, Nalchik for a cure and he was dispatched to Tbilisi to “settle” the issues.

Stalin had a careful speech, he played on national sentiments and mentioned the phrases such as “We, Georgians” several times but he was whistled already in the beginning and hardly managed to finish his speech. After him, the Mensheviks – Aleksandre Dgebuadze, Isidore Ramishvili and the others were met with great ovations. The legend says that the Russian workers were also involved in criticism and anti-Communist exclamations. “Get rid of us and take your Red Army with you!” – the influential Communist was seen off by such words. Stalin’s failure was followed by oppressions in the highest circles of Georgia – the head of the Revolutionary Committee of Georgia, Filipp Makharadze was dismissed and replaced by Budu Mdivani. [1]

Aleksandre (Sasha) Dgebuadze

Not only the Mensheviks and the politicans of the First Republic of Georgia, but also such influential representatives of Bolsheviks such as Filipp Makharadze emphasized the unpopularity of the Bolsheviks in Georgia. In a secret report, which was later published in press, he mentioned the the unpopularity of the Bolsheviks and for improving the situation, he suggested the implementation of different measures. [2]

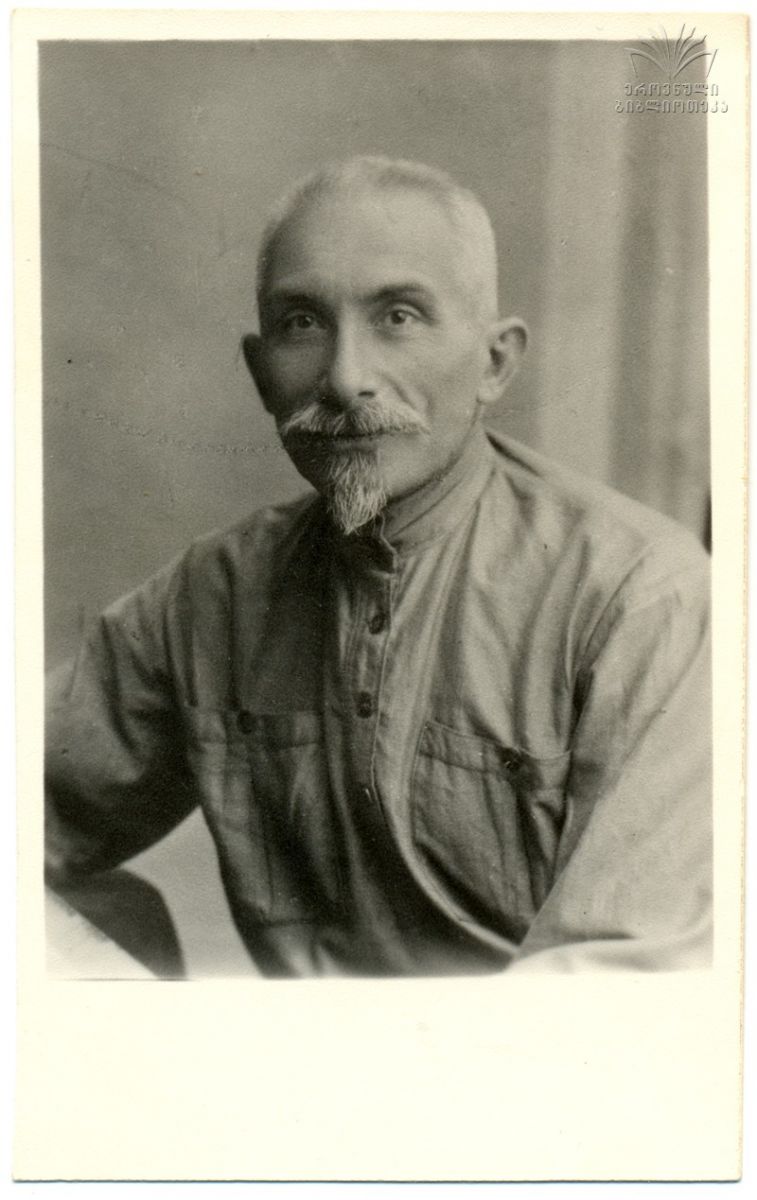

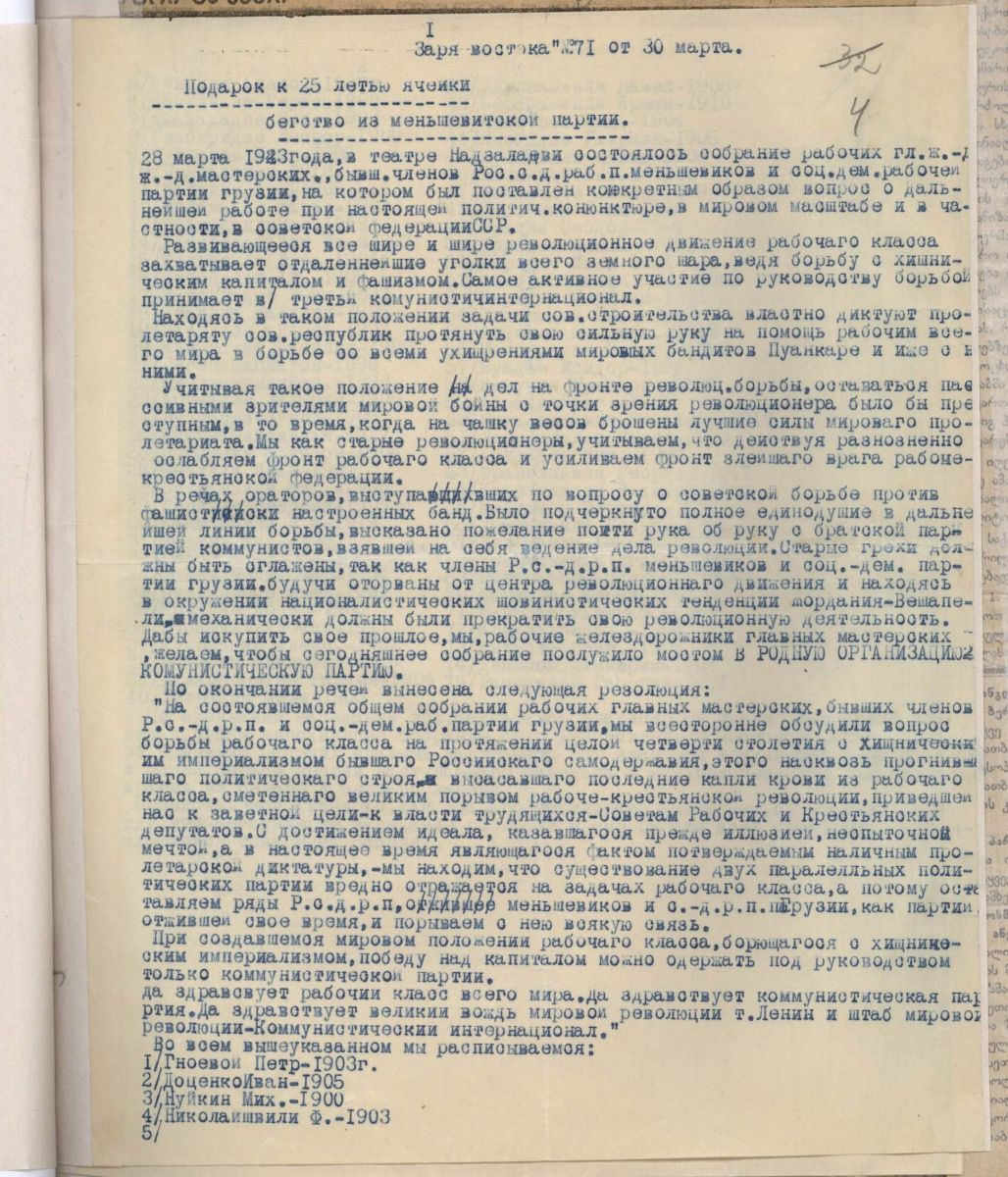

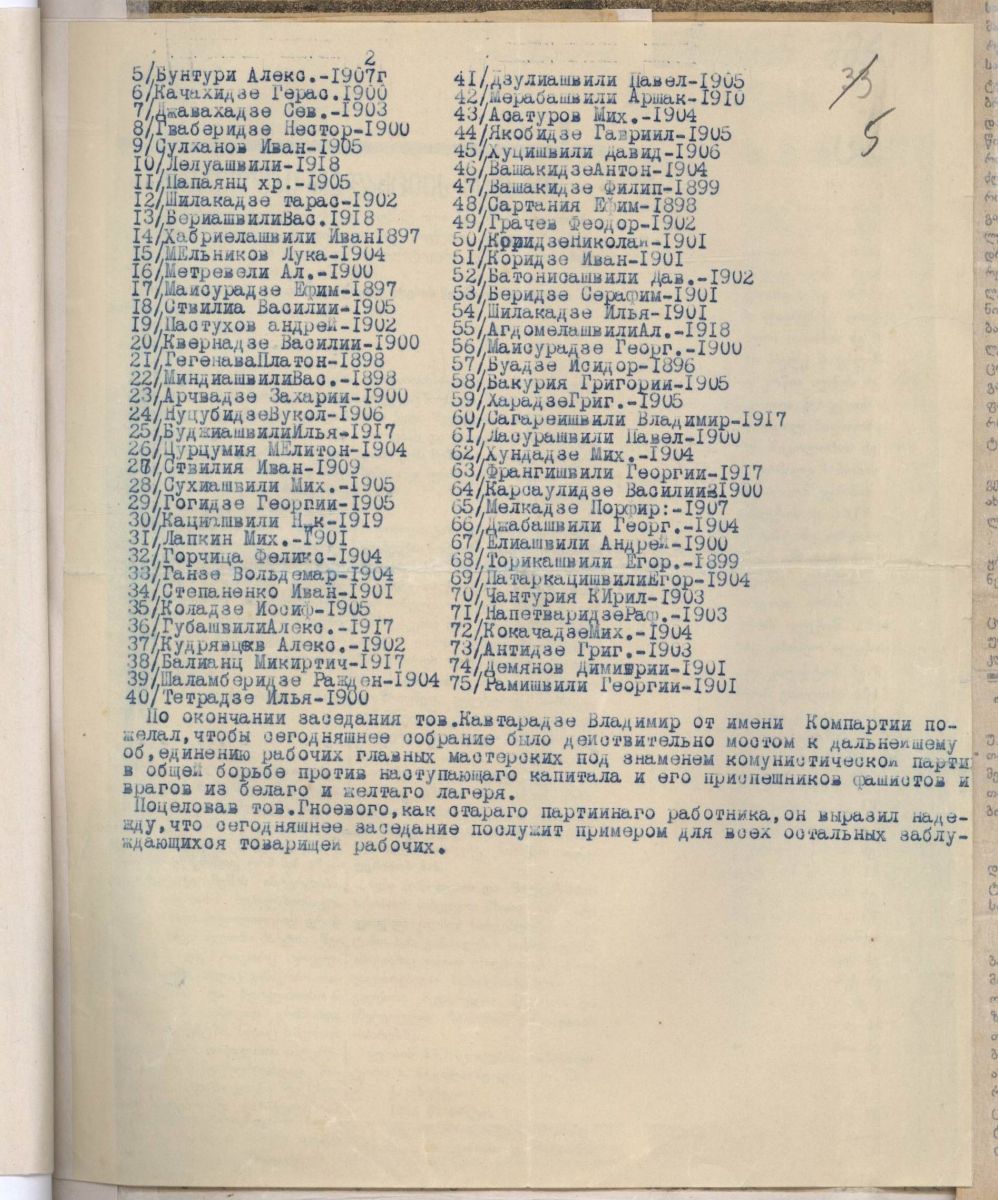

It was obvious that the Bolshevik’s goals in Georgia were not attained and the repressive measures were needed. First of all, through the influence of the Bolsheviks, an illusionary oppositional party was established in Georgia. On 28 1921, so-called “Menshevik Party” gathered at the same palace where the First Democratic Republic of Georgia declared its existence. Through the pressure from the Bolshevik regime and its security organs, Ioseb Machavariani, member of the Constituent Assembly, became the head of the party (he was shot in 1937 based on the decision of NKVD Troika). The results of the meeting that were published in the newspaper „ЗаряВостока“ interestingly portray this gathering. 75 delegates decided the liquidation of the Social-Democratic Party of Georgia and its unification with the Communist Party: “The revolutionary movement of workers slowly expands and covers distanced locations while fighting against predation and fascism. The key fighter in this struggle is the Third Communist International. While the best representatives of proletariat in involved in the struggle, we, as the old revolutionaries, think that through separated action we strengthen the front of an opponent”. [3] In the resolution, the block of Zhordania-Veshapeli [4] was mentioned as the outdated party, encircled by the nationalist-chauvinist tendencies, which was strange considering that these people had also gathered in the name of “Mensheviks”.

Assembly of the “Menshevik Party” at the Viceregent Palace (Contemporary Youth Palace), 28 March 1923

Article published by the “75 Mensheviks” about the dissolution of the party

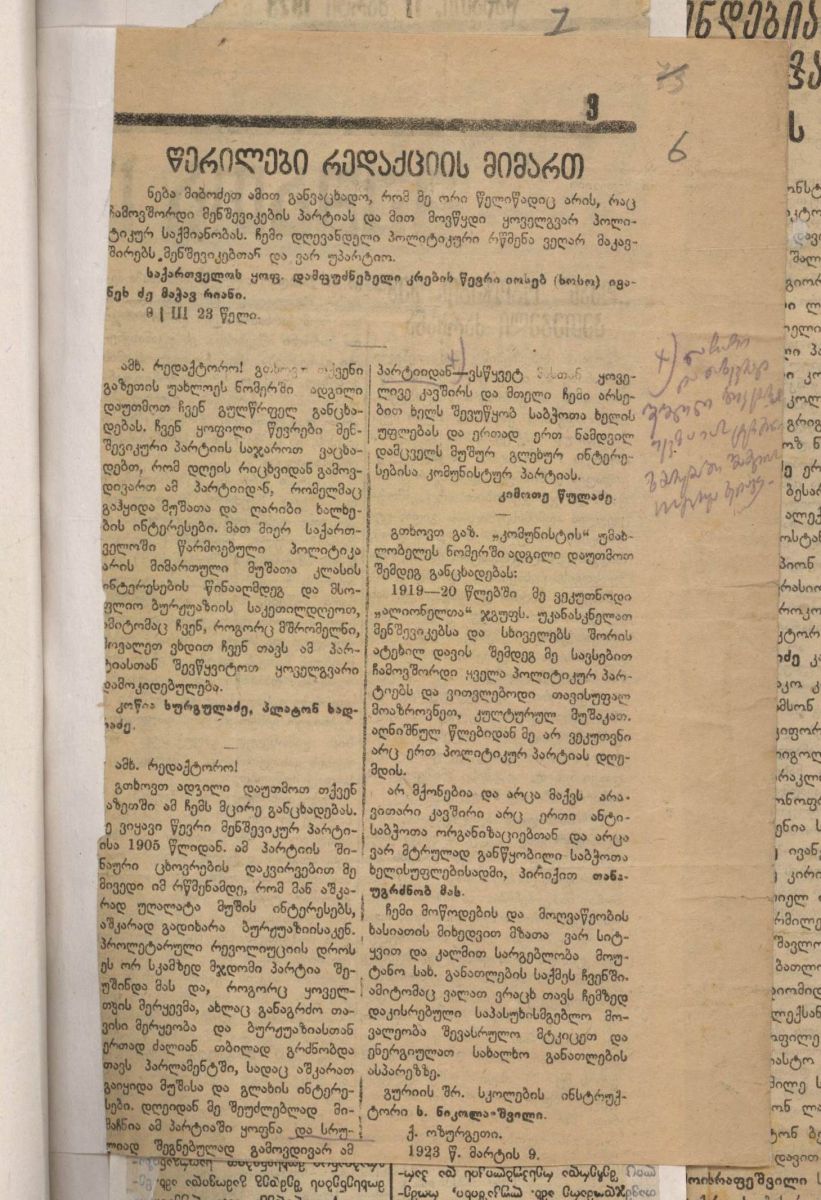

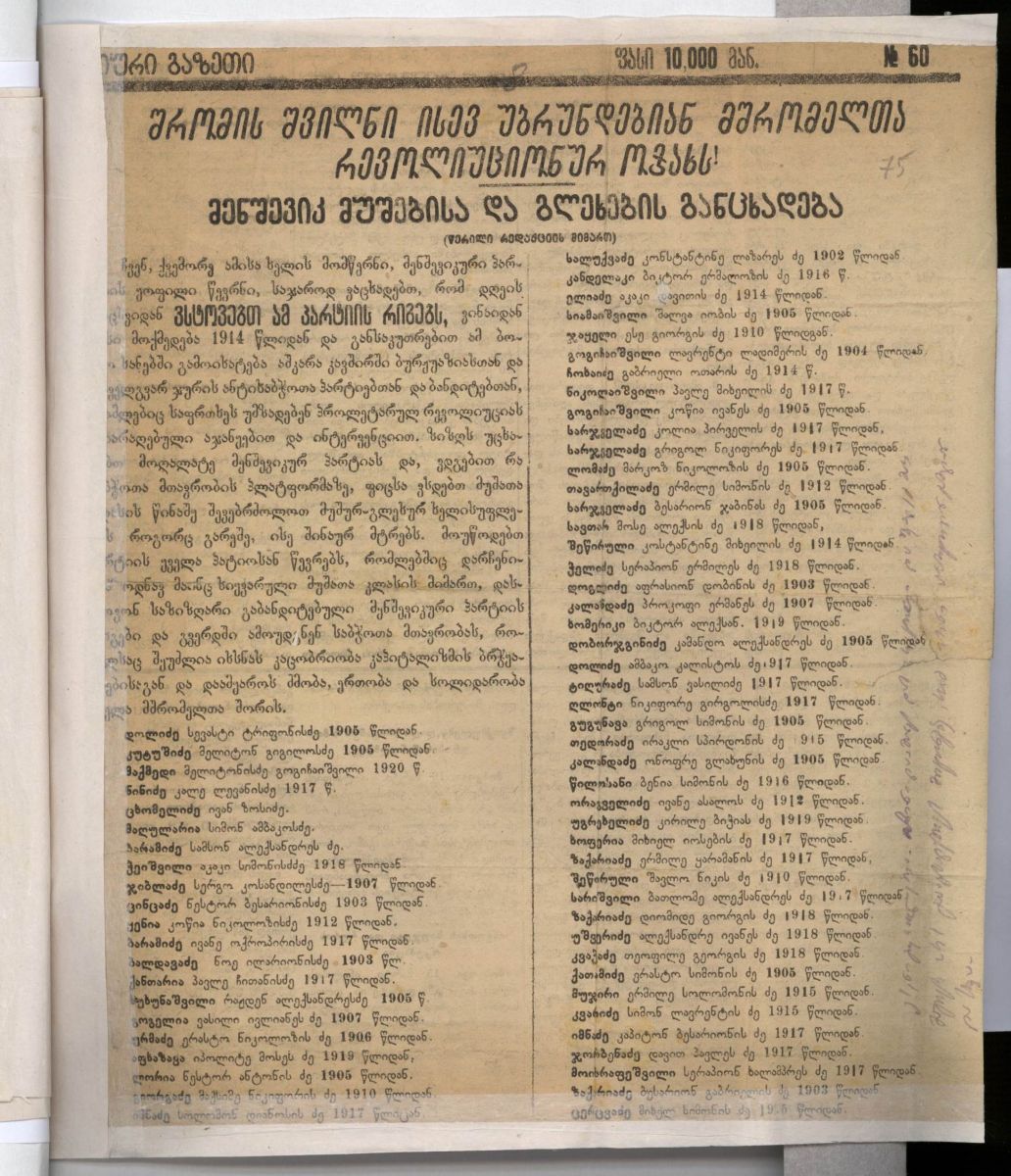

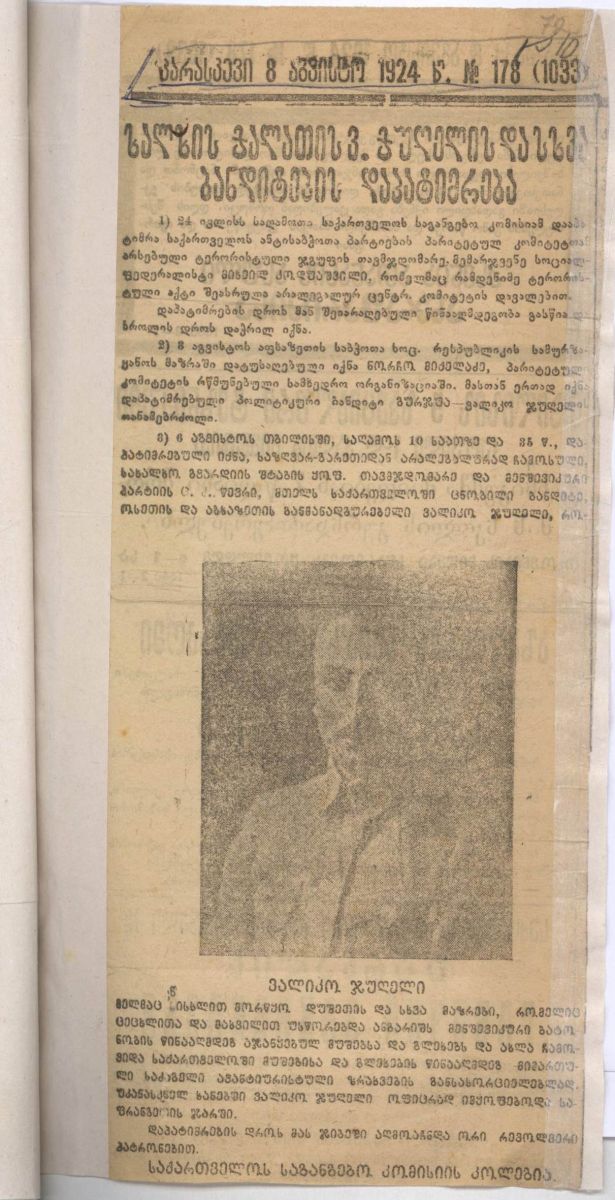

Many letters were published in the newspapers after the liquidation that were signed by individual members as well as the collective. “The letter by 66 Mensheviks”, “The Sons of Labor Return to the Revolutionary Family” and the other publications clearly show the growing terror in the society. Ioseb Machavariani, the highest official of Mensheviks, who moved to the Bolsheviks, also published a letter. After they came to power, they started the demonstration of the face of a winner power and moved to the active phase of terror. They started the physical liquidation of the most respectable groups of the society, military officials, clergy and former politicians:The Military Center, consisting of Konstantine Apkhazi and the 14 high-ranking military officials, was destroyed in 1923; Since 1921, strict measures were taken against the Orthodox Church of Georgia which continued with the punishment of the Patriarch, Ambrosi Khelaia after he sent a letter to the Genoa Conference; Several politicians and military officials, who had returned from the exile in France, were arrested in 1924: the head of the People’s Guard, Valiko Jugheli; the former governor of Tbilisi, Beniamin Chkhikvishvili and others. Jugheli’s arrest was thes greatest “trophy”. Articles about him was not only aimed against him but on the enhancement of public hatred: “On 6 August, at 10:35 in the evening, Valiko Jugheli, former head of the People’s Guard, member of the Menshevik Party, well-known bandit in the whole Georgia, the destroyer of Ossetia and Abkhazia, who has shed blood of many in Dusheti and the other districts and has illegally returned from abroad, was arrested…” [5] At the Cheka prison, through the apparent torture and psychological terror, Valiko Jugheli was forced to write several letter and these letters were published in the newspaper Communist. In the letters, Jugheli confessed his blame, and call for the society who had different opinions to rapidly adapt to the Communist regime.

.jpg)

The individual and collective “letters of confession” of the former Mensheviks

The articles aimed against the head of the People’s Guar of the First Republic, Valiko Jugheli from the newspaper – Communist

Arguably, the Bolsheviks attained the final victory over the Mensheviks in 1924 when they suppressed the national revolt. The revelation of rebels was significant in two ways: first, the Secret Service found all the members who operated in the underground in 1921-1924. All of them were either arrested, sentenced to death or resettled. On the other hand, the Bolsheviks gained total control over the opposition and not they had a chance to represent any types of oppressions against different opinions as a fight against Menshevism. If until 1924, they acted in a careful manner as they were afraid of the international resonance, in 1924, armed rebelion was publicly announced as counter-revolutionarism. After the failed attempt of rebellion, they used the well-tested method for punishing Valiko Jugheli. Through preassure, the forced the leader of the Independence Committee of Georgia, Konstantine Andronikashvili, secretary, Mikheil Javakhishvili and the others to publish a letter in the newspaper Communist.

The life and history of a founder the Republic of Georgia, Social-Democratic (Menshevik) Party were about to end. After the famous events of August-September 1924, the Georgian government in exile in France also abstained from sacrificing its members for inevitable death and since then, there were only several fights in Georgia against the Bolshevik government. The term “Menshvism” was preserved in everyday discourses for a long time and, as totalitarian regimes often do, it was used as an image of the greatest enemy. In 1928, the new term appeared next to it – “Trotskyism”.Many people were auccused of Menshevism for many years – from Ivane Javakhishvili, who was attacked by the historians at the Tbilisi State University, to the choreographer of National Ballet, Nino Ramishvili, who together with her husband, Iliko Sukhishvili was often reminded of her Menshevik kinship by the party officials. [6]

For instance, on 26 March 1936, the “Discussions about the Conditions on the History Front” started at the Tbilisi State University at which the rector of the university, Karlo Oragvelidze as well as the most of the speakers condemned Ivane Javakhishvili and his works. V. Tsintsadze said: “Javakhishvili wrapped in Menshevism, nationalism tries to prove the unity of the Georgian people in terms of resistance without internal class conflict… He tries to explain this by bringing cultural re-building from Europe and not Russia. Why he looks toward Europe and not Russia can be easily explained, because we know that the Mensheviks considered Russia as an enemy and escaped from its proletarian dictatorship and the Bolshevik party. Motivated by this, Pofessor Javakhishvili attempts to have links with Europe and represent Georgia as historically completely separated from Russia. It would not be unnecessary to mention that his Menshevist conception derives from his nationalist-bourgeois character, wanting to throw the majority of the society into the abyss through anti-Leninist notions”.

If during the Cold War, the Soviet government declared the West and the capitalist world as a major enemy, before that, the Menshevism served this purpose. In Tsintsadze’s speech, it is clearly visible that the negative meaning stamped to the word “Menshevism” and later to the word “West” was basically the same for the whole 70 years of the existence of the Soviet Union. Therefore, if during the Second World War, people were judged for their collaboration with Nazis and during the Cold War, for their links with the West, during the 1937-1938 repressions, that concerned more than 30 000 citizens of Georgia, the sentences of thousands of people were directly related to Menshevism. All of the members of the First Republic were annihilated. “Former Menshevism” together with the other accusations was a stamp in the records of many repressed individuals created by the Troika.

___________________

[1] See: Dimitri Silakadze, Anton Vacharadze, How Stalin was Met in Sovietized Georgia, “Istoriani”, November 2014, pp. 20-23.

[2] See: Filipp Makharadze’s secret speech to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party, 9th anniversary of the Sovietization of Georgia, 1981, pp. 5055

[3] National Archives of Georgia, f. N1861, d. N3, c. N148.

[4]Grigol Veshapeli (Veshapidze), named as one of the leaders of the party, also played important role in the exile: he was a member of the delegation of the Democratic Republic of Georgia in spring 1922 who was sent to the Genoa Conference for initiating Georgia’s case. He was an editor of “Akhali Sakartvelo” in Paris. Later, the relations between him and the Menshevik government became tense because he gave an interview to one of the European publications without agreeing this decision with the party. This resulted in physical conflict. In 1926, another Georgian migrant, Avtandil Merebashvili killed him. At the court, Merebashvili has a lawyer hired by the Mensheviks but there were rumors that Merebashvili was himself an agent of the Bolsheviks. [4]The emphasis on his figure together was Noe Zhordania was arguably related to his activities at the Genoa Conference.

[5] Newspaper “Communist”, N178, 8 August 1924.

[6] See: Iliko Sukhishvili, Memoirs, Tbilisi 2008.

[7] National Archives of Georgia, The Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N471, d. N19, v. N1, c. N1, pp. N14-15 (Discussions about the Conditions on the History Front).

___

Publication of this article was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries. The opinions expressed in this document belong to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) and do not reflect the positions of Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI). Therefore, OSI is not responsible for the content.