On 5-6 December 2019, with the financial support of the Open Society Institute – Budapest Foundation, the Institute for Development of Freedom of information (IDFI) held a conference on the Openness of State Archives and Memory Studies in the Former Soviet and Eastern Bloc Countries at the Courtyard Marriot Tbilisi. Up to 30 researchers, historians, and the representatives of civil society from all over the world participated in the conference. The represented researchers are the leading specialists of the respective field in their countries as well as globally. They have been working on the issues related to historiography and memory studies for years. In this direction, they have created numerous articles, carried out researches and implemented projects and activities. Most of them teach at the top-ranking public and private universities and work on researches at leading institutions. The introduction of the research potential of the Georgian archives to them and their inclusion in the project was the major goal not just of the conference but of the project in general which has been implemented successfully. The invited specialists have emphasized that this project, aimed at the representation of the specificities of particular archives and the challenges the researchers face while visiting the closed archives, will help them and especially young researchers, visiting the archives for the first time, in planning their research. During the conference, various joint interdisciplinary researches and events were planned. The most important is the planning of the joint memory politics research for which the analyst of IDFI, Megi Kartsivadze will create a methodology.

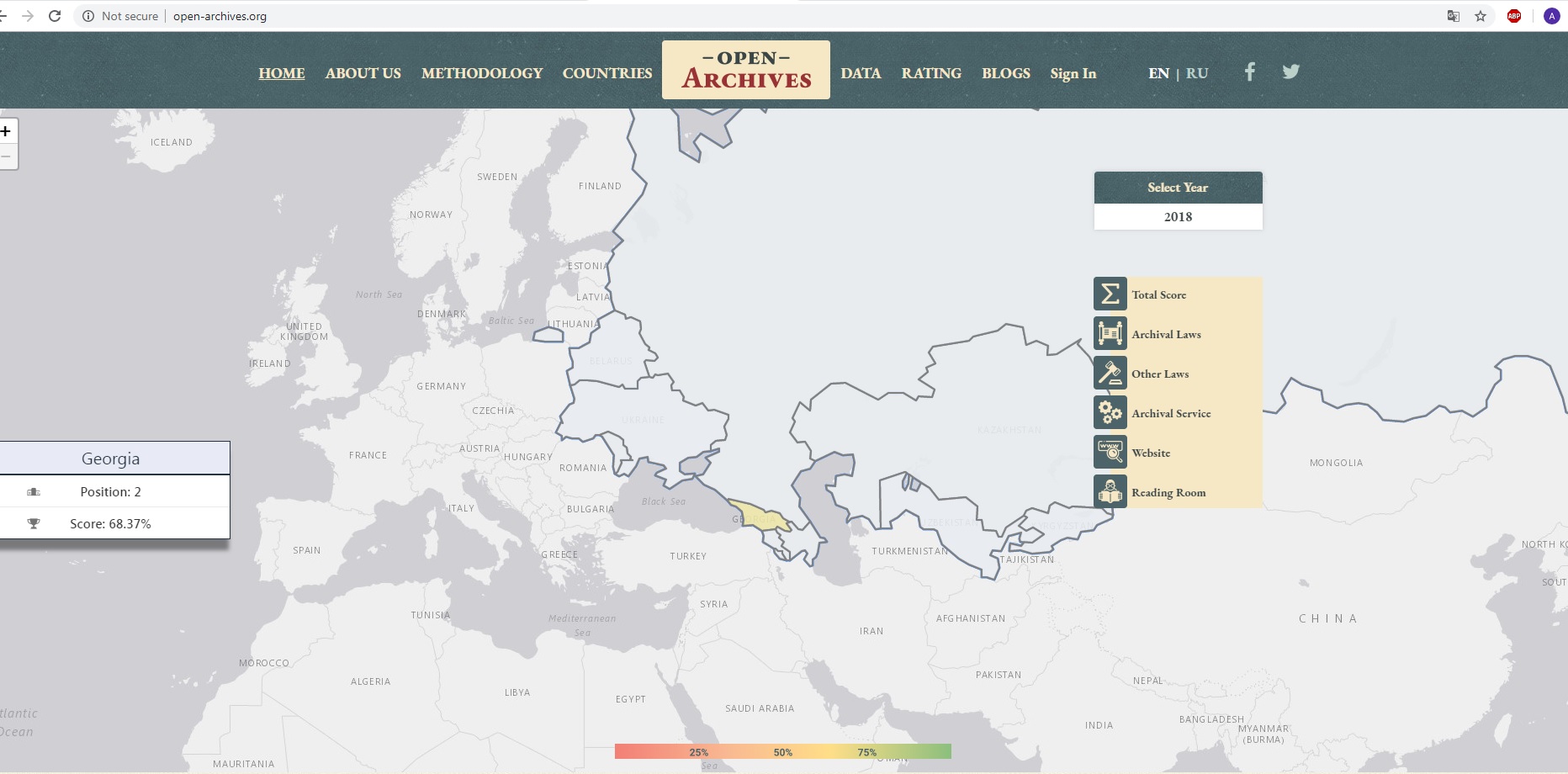

The network of open archives was created in 2017-2018 within the framework of an analogous project. In the beginning, it covered 10 post-Soviet countries while in 2019, 8 new countries of Eastern Europe were added to the project. The network of open archives includes the evaluation of 2 state archives in each country. Out of these archives, one is a central or historical archive and another one preserves the documents of the security services of totalitarian regimes (for instance, the materials of KGB). The evaluation is carried out according to the universal methodology, which results in the creation of the ratings of archives as well as countries. Based on the rating and the challenges revealed in particular archives, the members of the network advocate the openness of state archives considering the best international practices in their countries.

The first day of the conference was entirely dedicated to the openness of state archives. The Head of Archives, Soviet and Memory Studies direction at IDFI, Anton Vatcharadze welcomed the guests and expressed gratitude towards them for attending the event. After that, the Director of the Archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, Omar Tushurashvili made a speech in which he also welcomed the participants and briefly outlined the importance of such projects and discussions for enhancing the openness of state archives. Moreover, he invited the attendants at the MIA Archives to introduce the working principles of the archives and the documents preserved there to them.

The first day of the conference was divided into four panels, covering the challenges to the access to state archives in the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries, legal regulations, best international practices and the role of archives in memory studies. On the first panel, chaired by Doctoral Candidate in History at the University of Cambridge, UK, Sarah Slye, Linda Norris (Director of Global Networks, International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, US), Pavel Zacek (MP of the Czech Republic/ Lecturer in CEVRO Institute), Giorgi Mamulia (Researcher, Higher School of Social Sciences (EHESS), France) and Gints Zelmenis (National Archives of Latvia) discussed the best international practices of the accessibility of archives.

Linda Norris talked about the work of the “Coalition of Sites of Conscience”, aimed at activating the power of places of memory to engage the public in connecting past and present in order to envision and shape a more just and humane future. She shared the experience of the coalition in modernizing, restructuring and enhancing the openness of archives and museums. Linda Norris provided examples of the archives and museums in Argentina, Guatemala, Sierra Leone, Ukraine, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, Bangladesh, Kenya, Italy, and the US. Her presentation showed how the different countries of different continents instrumentalize the memory sites for dealing with the traumatic experiences of the recent past.

Pavel Zacek, who was the founder and the first director of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes and the Security Services Archive in the Czech Republic, shared his experience on the enhancement of the accessibility of state archives. He described in detail how the Czech Republic has opened the state archives after the Velvet Revolution. As long as the archives of the Czech Republic can be considered as one of the best examples of accessible archives in the region, Pavel Zacek’s presentation was useful for the auditorium, focused on the identification of different ways for making the archives more open to the wider public.

Giorgi Mamulia talked about the archival materials preserved at the French archives. He introduced the acceptance rules and regulations at these institutions. Mamulia provided examples of several researches he has carried out at the French archives. His presentation contained valuable information about the best practice of the open archives which can serve as an exemplary model for the other countries.

Gints Zelmenis is a member of the Latvian National Archives who was responsible for publishing the KGB materials preserved there in 2018. This step has not yet been taken by any of the former Soviet Union or Eastern Partnership countries, and this is the best example of archival openness in the region. He talked about the challenges in this process and shared his experience with the attendants.

Levan Avalishvili, Co-Founder and Programs Director at IDFI chaired the second panel about the legal regulations and practice of access to archival documents. Evgeni Smirnov (Lawyer, Team 29, Russian Federation) and Nino Merebashvili-Fisher (Senior Lawyer, IDFI) discussed different legislative practices related to archives and memory studies while Elmira Nogoibaeva (Director of the analytical center „Policy Asia“) introduced the platform Esimde for studying the history and memory of Kirgizstan and Central Asia.

Evgeni Smirnov, based on his and his team’s experience, made a presentation about the legal regulations on access to archives in the Russian Federation. He described the challenges researchers and not only face in Russia while attempting to get access to particular documents containing personal data, state secrets or other types of information hidden by the state. His presentation was a great example of the problems in the archives of the post-Soviet countries that need to be overcome.

Nino Merebashvili-Fisher talked about the legal case IDFI won against the National Archives of Georgia at the Tbilisi City Court as the court ordered the respondent party to disclose information on the number of applications received with the request of accessing archival documents and relevant decisions taken. Additionally, she presented about the legislative proposal IDFI had submitted to the Parliament of Georgia on the amendments in the law on National Archives and personal data protection. Although the proposal has not been accepted by the Parliament, IDFI continues working on it and therefore, the discussion about it with the experts from different countries was of crucial importance.

Elmira Nogoibaeva made a presentation about the discussion platform Esmide. Esmide’s primary goals are the rethinking of the history of Kirgizstan and Central Asia, establishment of historical truth, enhancement of the study of the history of Kirgizstan in the XX-XXI centuries, finding the new interdisciplinary methodologies and approaches to memory studies. Elmira Nogoibaeva’s presentation was interesting inasmuch as it provided information about the new institutional form of memory studies in Kirgizstan and created a space for future collaboration with it.

On the third panel, the panelists discussed the challenges to access to state security archives. The panel was chaired by Anna Oliinyk, Director of the Center for Research on the Liberation Movement, Ukraine. Andriy Kohut (Director of the SBU (former KGB) archives of Ukraine), Dmitriy Drozd (Researcher of the Belarusian Documental Center) and Eldar Zeynalov (Human Rights Center, Director, Journalist, Azerbaijan) participated in the discussion.

Andriy Kohut talked about the changes in access to archives in Ukraine since the end of the 1980s until today. He divided this process into four periods between the end of the 1980 and the 1990s, 2004-2010, 2010-2014 and 2014-2019. First, Kohut described the transition period and how the KGB archives were transferred to state archives. Then he provided information about the creation of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory. After that, Kohut talked about the process of digitization of archival materials and de-Communization. Kohut also provided valuable information about the legislative initiatives and amendments related to archival works. As long as, according to IDFI’s international rating, Ukraine holds the leading position in the openness of state archives among the post-Soviet states, Kohut’s presentation contained valuable information for the post-Soviet countries, attempting to enhance to the accessibility of their archives.

Dmitriy Drozd made a presentation about the legal difficulties in accessing the state archives in Belarus. He provided detailed information about the legislative restrictions for which the Belarusian archives hold one of the lowest positions in IDFI’s ranking of archives. Such restrictions include the classification of the documents as state and personal secrets and the regulation which restricts the researchers to use the documents that contain personal data if 75 years after their creation have not passed. He also talked about the political situation in the country and Lukashenko’s personal attitude toward Stalin’s figure and Stalinism, which further complicates the implementation of effective memory politics in the country, aimed at the rethinking of the Soviet past and legacy.

Eldar Zeynalov talked about the problems in Azerbaijan in terms of the formation of the collective memory. He mentioned that the closed archives that are used for political objectives make it impossible to rethink the Soviet past and evaluate the event objectively.

The final, fourth panel of the first day was focused on the role of archives in memory studies. The panel was chaired by Oliver Reisner, Full Professor in European and Caucasian Studies, Ilia State University, Georgia. The panelists - Jan Rachinsky (Head of the Board of the International Memorial, Russian Federation), Stanisław Koller (Department of Archival Research and Source Edition, National Remembrance Institute, Poland), Hranush Kharatyan (Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia), Vytautas Starikovičius (Lecturer at Vilnius University, Department of History and Lithuanian Museums' Centre of Information, Digitisation (LIMIS), Lithuania) and Anna Oliinyk (Director of the Center for Research on the Liberation Movement, Ukraine) – shared the experience of the respective countries with the audience.

Ian Rachinsky talked about the high level of politicization of history, memory studies and also archives in Russia. He provided various examples of how the commemoration is used by the government as a tool for justification of its supremacy. His key argument was that the open archives have paramount importance for revising the politicized history. Ian Rachinksy also discussed various legislative as well as procedural challenged to the access to state archives, which further complicates the process of rethinking and revaluating the recent history of the country.

Stanisław Koller’s presentation was focused on the importance of the Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance in keeping and restoring the memory about the crimes of the Nazi and Communist regimes and their victims. He described hoწ the institute dealt with the investigation of the crimes committed by the totalitarian regimes, collection of archival materials, lustration, identification and rehabilitation of victims, educational projects and historical research. Koller also provided information about the challenges the institution faces in terms of location, archival fonds, disclosure of agents, etc. However, the Institute of National Remembrance in Poland and the information about its work can be valuable for the other countries in the region that lack the comprehensive institutional approach to memory studies.

Hranush Kharatyan talked about the Armenian archives as one of the most important guarantees of the formation of the national memory. According to her, the Armenian National Archives and the Archives of the former Security Committee play a major role in this process. She mentioned that, without these archival documents, the creation of a so-called national narrative is impossible.

Vytautas Starikovičius talked about the new approaches in the era of digitation of archival materials, based on the experience of Lithuania. He provided information about the web site of The International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania, KGB activity in Lithuania and the accessibility of the KGB files online. His presentation also contained information about virtual exhibitions that can be used for increasing the impact of memory sites in society. Vytautas Starikovičius’s presentation suggested the new approaches to digitation practices that can be used by the other countries for making their archives more easily accessible to the wider public.

Anna Oliinyk made a presentation about the project by the Center for Research on the Liberation Movement in Ukraine which made a special course for the journalists from Ukraine, Poland, Czech Republic, and Slovakia on the archival work. Within the frame of this course, the journalists were instructed on how to work on archival materials and how to use them in media. As a result, more than fifty pieces of work were published and some journalists continued working in this field. Additionally, Anna Oliinyk talked about the creation of special textbooks and online courses for instructing everyone interested in archival work on specific procedures and approaches. This presentation was inspiring inasmuch as the similar initiatives in the represented countries can considerably contribute to the accessibility of state archives.

The second day of the conference was dedicated to memory studies, which is a new component of the project. It is aimed at popularizing the archives-based research in the society and the rethinking of totalitarian past. The second day was opened by the panel on institutional and state memory politics in the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc Countries. The panel was chaired by Nutsa Batiashvili, Dean of Graduate and Doctoral Programs, Free University of Tbilisi, Georgia. Alexandru-Murad Mironov (History Department Faculty Member, University of Bucharest, Romania), Said Gaziev (Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Asian and African Studies, Graduate Student, Uzbekistan), Ewa Ochman (Senior Lecturer in East European Studies, The University of Manchester, UK), Megi Kartsivadze (IDFI, Georgia) and Igor Casu (Historian, Center for Study of Totalitarian Regimes and Cold War, State University of Moldova) participated in the discussion.

Alexandru-Murad Mironov made a presentation about the memory politics implemented in Romania after the fall of Communism. His speech covered the work of the Romanian Academy and its institutes of historical research, former ideological academic centers, museums, universities, research centers, and archives. Mironov’s presentation provided valuable information about the memory politics in Romania which can be used for comparative analysis in the future.

Said Gaziev talked about the recent changes in Uzbek state archives. His presentation outlined that despite the transformation of the Soviet archives, the Soviet-style prohibitive attitudes have remained which affects the accessibility of the archives. Said Gaziev also discussed the restrictive legislature related to archival work and the conditions of archives together with ineffective management. His presentation was yet another example of the problematic state of the archives in the post-Soviet space.

Ewa Ochman is a professor at the Manchester University, working on the Polish memory studies. She made a presentation “The Recovery of Forgotten Past – Polish Experience”. Ewa Ochman is an author of publications: “Reconciliation across the border: Polish-Russian relations and historical memories of the Polish-Soviet War”, “Memory in Poland before and after Crimea: Legislating the De-Communization of Public Space”, “Spaces of Nationhood and Contested Soviet War Monuments in Poland: The Warsaw Monument to the Brotherhood in Arms”.

Megi Kartivadze’s presentation covered the memory politics implemented in Georgia after 1991 in four dimensions: legal, institutional, commemorative and monumental. She talked about the legislative initiatives and amendments as well as the establishment of the institutions defining the state memory politics in Georgia. After that, she discussed the holidays, street names and monuments commemorating the problematic past of the country. Apart from that, Megi Kartsivadze’s presentation contained the comparative analysis of memory politics in Georgia and the Baltic countries, which creates a further space for comparing the memory politics in different countries.

Igor Casu talked about the activity of the presidential commission for the study of the communist totalitarian regime and the opening of KGB and MVD archives in Moldova and the reasons for its partial failure. He argued that the lack of agreement among MPs resulted in the delay of passing necessary law. For this, there is no law in Moldova, which would establish a separate KGB/MVD archive or facilitate the openness of related archives. He emphasized that corruption among elites is yet another problem, which affects the effectiveness of memory politics in the country while the lack of funds and political will results in the absence of a research institution, which would research the Communist past.

The second panel was about shared memory after the end of the totalitarian communist era. The chair of the panel was Tamta Khalvashi, Associate Professor, Ilia State University, Georgia. Mischa Gabowitsch (Researcher, Einstein Forum in Potsdam, Germany), Alexandra Tsay (Cultural studies researcher, “Open Mind”, Kazakhstan), Sandor Horvath (Head of the Department for Contemporary History, Institute of History of Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary) and Edgars Engizers (Faculty member, Baltic International Academy, Latvia) participated in the discussion.

Mischa Gabowitsch made a presentation about what has happened to Soviet war memorials from 1989-1991. He discussed the different ways in which memorials had been treated. His analysis encompassed historical background; the legal context, institutions, and inventorying efforts; new construction and reinterpretation; destruction, removal, and modification; and artistic interventions. Based on extensive examples from the Soviet Union, post-Soviet space, Central and Eastern Europe, Gabowitsch argued that centralized removal campaigns have been an exception rather than the norm.

Alexandra Tsay talked about the role of artists in memory studies. She discussed them as memory activists and art as a medium of collective memory in Kazakhstan. She argued that the main purpose of their work was to revalue Stalinism from a different perspective and attract the interest of the younger generation. Alexandra Tsay’s presentation included the works of Oleg Karpov, Alexander Ugai, Roman Zakharov, Zoya Falkova, Said Atabekov, Asel Kadyrkhanova. The artistic commemoration and evaluation of the traumatic past suggested by Alexandra Tsay is another interesting initiative that can be useful for the represented countries looking for new approaches to advance their memory politics.

Sandor Horvath one of the members and a curator of the innovative project “Cultural Opposition - Courage – Connecting Collections”, aimed at creating collections and united European archival space. Through this project, the European archival documents become accessible online and any researcher will be able to create scientific as well as popular articles and carry out historical innovative projects using their computers only. Sandor Horvath suggested the participants get involved in this project and expressed his willingness to support them in this process.

Edgars Engizers made a presentation about the shared memory after the end of the totalitarian Communist era in Latvia. He described hoe the pre-World War II narratives were evoked after the fall of the Soviet Union and how the Soviet historiography was rejected amid the growth of nationalism. Engizers showed how the Westernization and “Hollywoodization” penetrated the Latvian shared memory. He also emphasized that the opening of KGB archives for research in 2014 and unfinished research supported by the government in 2018 resulted in the condemnation of KGB agents without understanding the KGB and LCP and CPSU and Soviet system behind them. Moreover, he talked about the Kremlin’s memory war in Latvia, aimed at the glorification of the Soviet past.

The final panel of the conference, chaired by Anton Vatcharadze, Archives, Soviet and Memory Studies Direction Head at IDFI, Georgia, was about forgetting the crimes of totalitarian regimes and how to avoid it. The participants were Momchil Metodiev (The Institute for Studies of the Recent Past, Researcher, Bulgaria), Meelis Saeuauk (Senior Researcher, Institute of Historical Memory, Estonia) and Parviz Mullojonov (Visiting researcher of the University of Uppsala, Sweden/Tajikistan).

Momchil Metodiev’s presentation covered an interesting period from the history of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. He talked about the ministers who had been recruited by the security services for acquiring the secret information sent abroad. According to Metodiev, as a result of working in the archives, he has published materials proving that 11 out of 15 ministers at the Bulgarian Orthodox Church collaborated with the security system. He also introduced the practice of the totalitarian regimes used for recruiting religious leaders to the audience.

Meelis Saeuauk works at the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory. This institute is one of the best institutions, which has done a lot in terms of rethinking the past, and proactively shares its experience with other countries. For the next 5 years, the institution plants to reconstruct one of the biggest Patarei Prison as a memorial of the victims of communism and link the organizations throughout Europe, working in this direction, with one another. Meelis spoke about the institute and its projects.

Parviz Mullojonov talked about the role of the contemporary Russian government and local elites in the de-Sovietization of Tajikistan. He emphasized that the Russian government hinders this process for several reasons: geopolitical aspirations, idealization of common past, concerns over losing the cultural influence and positioning of the soft power on conservative and communist roots. Mullojonov also discussed the dual approach to the historical memory of the local elites that are ideologically close to their Russian counterparts. His presentation was very timely inasmuch as Russian soft power becomes a more influential factor affecting the state memory politics and memory discourses in the region every day and it would be beneficial to include it in the final joint report.

The conference was closed by the roundtable discussion attended by all of the participants and led by Mischa Gabowitsch. The participants discussed the implementation of memory politics in the region and beyond. Some of the attendants have also announced interesting initiatives and suggestions. Mischa Gabowitsch invited the participants to submit their papers to the Fourth Annual Memory Studies Association Conference at the University of Virginia, held on 18-21 June 2020. He also announced that the call for papers for the first regional conference organized by the working group on Post-Socialist and Comparative Memory Studies, scheduled on Sep 24-26, 2020, in Chisinau, Moldova would soon be published. Moreover, Anna Oliinyk also spread information about the planned conference in Ukraine, presumably in August 2020, on the topic “How to deal with the past?” Elmira Nogoibaeva also announced that there would be a conference in Central Asia about memory studies which will be focused on the phenomenon of “Mankurt”.

Finally, the participants of the conference agreed to continue advocacy of the openness of state archives in the respective countries. Anton Vatcharadze also introduced the electronic system for evaluating the openness of archives to them. The participants will insert their data into this system and the final joint report will be prepared based on the accounts provided there.

Apart from the discussions, the participants of the conference visited two institutions – The National Museum of Georgia and the Archives of the Communist Party preserved at MIA Archives. At the National Museum, they observed the exhibition of the Soviet Occupation. At the MIA Communist Party Archives, they saw the documents, they had discussed with the director of the MIA Archives, Omar Tushurashvili at the conference, thematically. At both of these institutions, the discussions and debates about museums, memory, archives and the Soviet past continued and the participants exchanged ideas with one another as well as with the management of the institutions.

___

The conference was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries.