08 September 2017

Author: Anton Vatcharadze - Head of the Archives, Soviet and Memory Studies Direction at the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), Ph.D. Candidate at the Ilia State University.

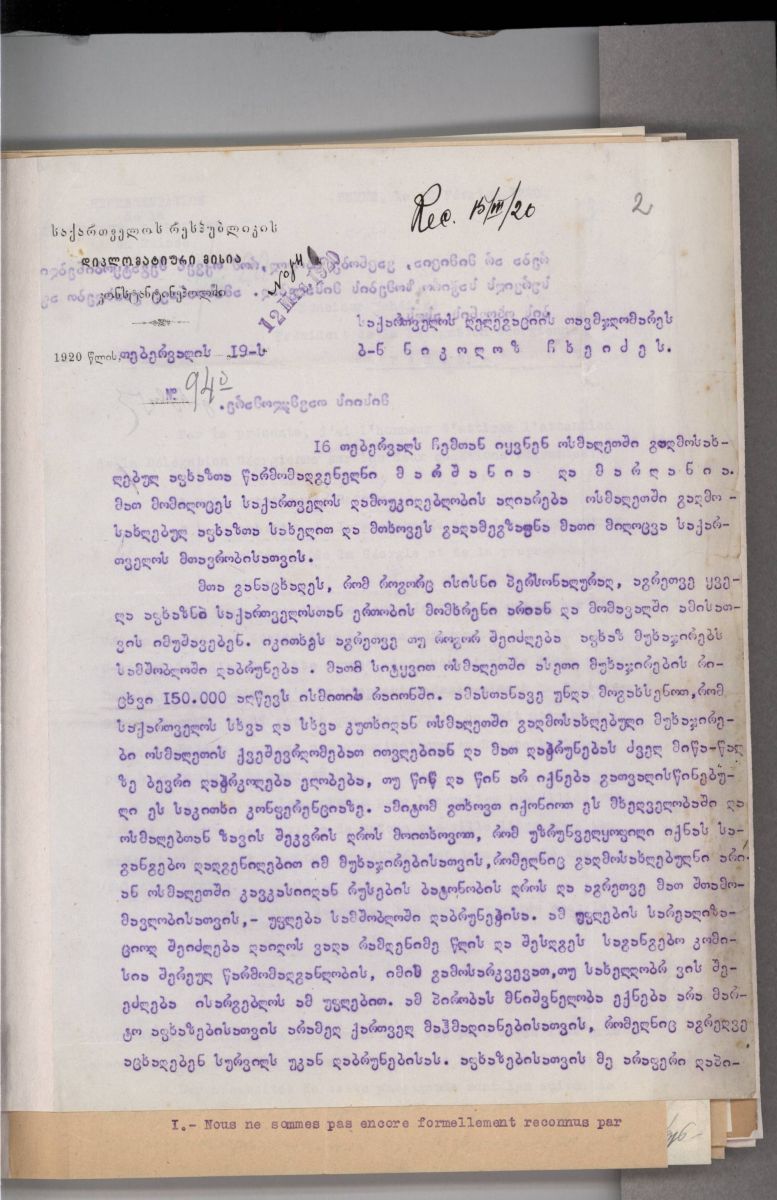

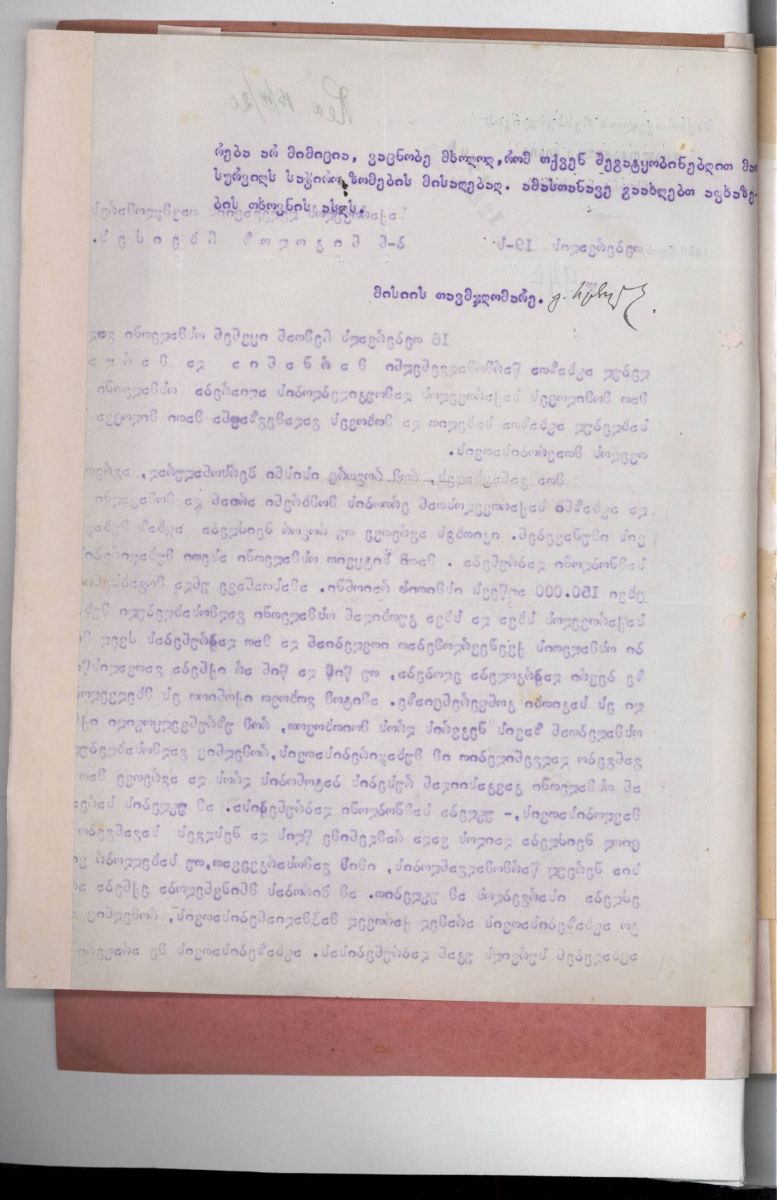

On February 19, 1920, representatives of Abkhaz Muhajirs, Marshania and Marghania, visited the chairman of the Diplomatic Mission of the First Democratic Republic of Georgia in Constantinople, Grigol Rtskhiladze. They congratulated Georgia with the declaration of independence and informed the government of Georgia that 150,000 Abkhazians expressed their desire to return to their historical homeland: "They stated that they personally, along with all Abkhazians, are in favor of unity with Georgia and will work towards achieving this in the future. In their words, the number of such Muhajirs in the Ottoman Empire reaches 150,000... therefore, please take this into consideration, and, during peace treaty negotiations with the Ottomans, request a special resolution for Muhajirs and their descendants who were resettled in the Ottoman Empire during the Russian domination in the Caucasus guaranteeing their right of return to their homeland”. (Source: The National Archives of Georgia, Central Historical Archive, Fund 1864, Inventory 2, Item 296, page 2-2a).

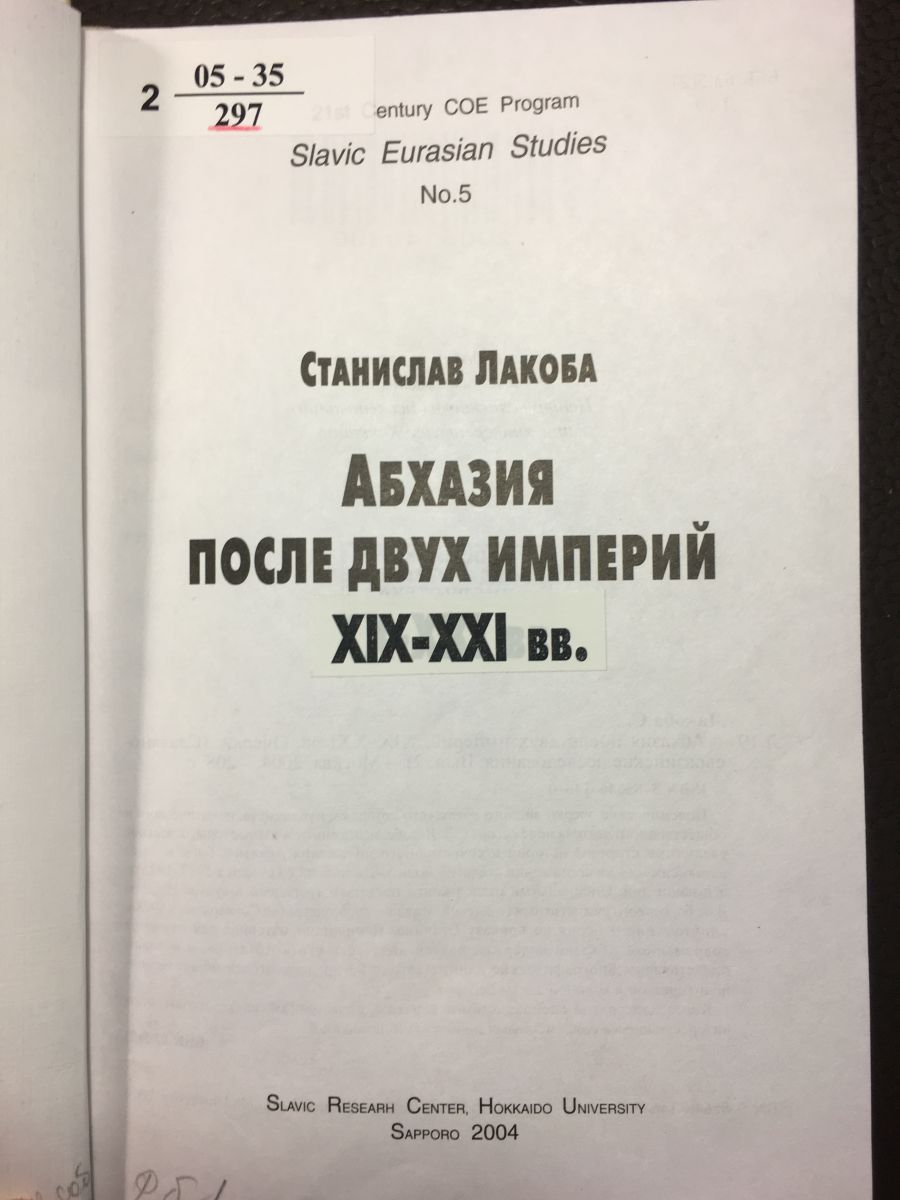

The document preserved atthe National Archives of Georgia

The forced emigration of the Muslim population from the North Caucasus and Abkhazia by the Russian Empire, so called Muhajirstvo had become a regular process since 1860s. According to various statistics, the number of resettled Abkhazians reaches tens of thousands and in total more than 60% of ethnic Abkhazian population was resettled. In 1866, the Russian Empire suppressed uprisings of Abkhaz people against Muhajirstvo by military force. With the results of this process, Russian Empire threatened Abkhazian population and nearly exterminated it, as well as, for example, another Caucasian ethnic group - the Ubykhs.

In the speech of the President of the Russian Federation, no word has been said about the Muhajirs and the crimes against Georgian, Abkhaz and other peoples committed by the Russian empire and the Soviet Union. On July 9, 2019, Vladimir Putin devoted an address to the ongoing events in Georgia and offered a different interpretation of the last 200 years history: "After World War I, Georgia made attempts to absorb Abkhazia, аn independent Georgian statewas formed and with the help from German troops, Georgia occupied Abkhazia in 1918 "

Abkhazia had been one of the strategic regions of Georgia andthe whole Caucasus during the First Republic. In the struggle to control the region, regular troops of Georgia were involved, as well as Denikin's "White Movement" from the Russian side, trying to invade and control Abkhazia. Additionally, local Bolsheviks, in which Abkhazian, Georgian and other ethnic groups were a part of, were trying to seize control. The situation was extremely tense in 1918 - local Bolsheviks, supported by the Russian Bolsheviks, started a rebellion against the Transcaucasian Sejm. On April 11, they departed from Gudauta towards Sokhumi, took control over the city, and created the "Sokhumi Commune". Georgian army was able to ease the situation, establishing full control over Abkhazia and expelling the Bolshevik forces. Here, we should take one more fact into account: The Ottomans tried to exploit the situation, and on June 27th, one thousand military personnel led by General Vehib-Pasha landed nearthe estuary of the Kodori river. However, the hostile reception by the local population and the immediate actions of the Georgian armed forces did not allow this force to act. The troops were given a proposal to leave the territory of Georgia within 24 hours, after which Turks were forced to turn back.

There area lot of documents similar to what we’ve presented in the beginning of our article,and for further study ofthese materials,visit: http://ava.ge/index/index.This website was created with funding from the Georgian President’s Administration. Archival and photo/video materials are available in Georgian, Abkhaz and English languages. Accordingly, the term "absorbing" voiced by Vladimir Putin is only replicating the propaganda history led by Russia’s interests and is part of the Informational War by the Russian Federation. Within the scientific study of archival documents, such an interpretation of Georgian history can be easily disregarded.

Unfortunately, the First Democratic Republic of Georgia failed to maintain its independence. In February-March 1921, the Bolshevik Red Army invaded from the south as well as from Abkhazia and occupied the entire country.The issue of the return of Muhajirs to their homeland and the prospect of Abkhazian development as one of the main autonomous republics inthe composition of a democratic, European Georgian state remained only on paper.

___

Publication of this article was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries. The opinions expressed in this document belong to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) and do not reflect the positions of Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI). Therefore, OSI is not responsible for the content.