03 May 2022

The fight against censorship and for the freedom of speech counts centuries. One of the most ancient cases of censorship is related to the philosopher, Socrates who was sentenced to death in 333 BC for spreading the ideas among the youth that opposed his contemporary moral and political code.

In XV century, the invention of print media increased the necessity in the church to strengthen the censorship. Catholic as well as Protestant Churches successfully used the printed materials for spreading their dogmatic. For instance, in 1559, Pope Paul IV was the first to publish the list of banned books. The Church fought against an access to prohibited books through its control on universities.

In 1766, Sweden abolished censorship and became the first country to defend the freedom of press through legislature. The enlightener thinker and liberal pastor, Anders Chydenius played an important role in this process inasmuch as it was his ideas that influenced the Swedish Parliament which adopted the “Act of Freedom of Press”. Today, this act is considered to be the first law on the freedom of information. Based on the decision of the Parliament, the censorship on all kinds of press was abolished, including the press imported from abroad. However, this did not concern the academic and theological works. Additionally, according to this act, access to the documents created by the government was ensured. In 1809, Sweden adopted the new Constitution, which included the main principles of the Act of 1766 and in 1810, the censorship on academic and theological works was also abolished. Chydenius’s legacy was soon acknowledged all over the world and nowadays, freedom of information is considered the norm of international justice. In 1770, Denmark and Norway followed Sweden, in 1787, the first amendment in the USA Constitution was adopted, according to which the freedom of speech and press was fully granted. Since the 19th century, independent press has appeared in the world, which significantly influenced the Russian Empire and also Georgia, which was incorporated into the Russian Empire at that time.

The collage of newspapers and journals published in Georgia. Source: National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

The history of the Georgian Press and Censorship

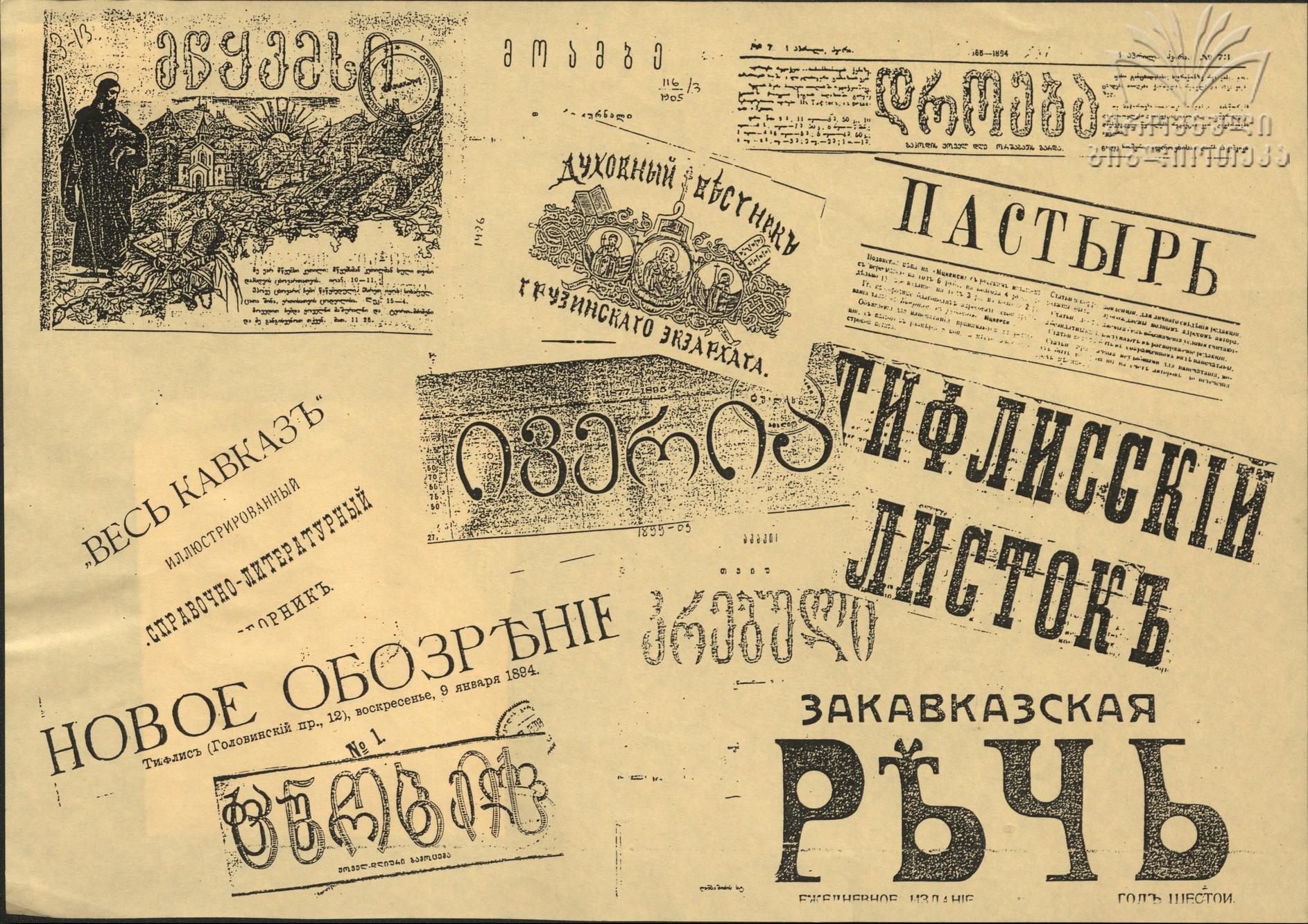

200 years ago, on 21 March 1819 (8 March according to old style calendar), the first Georgian print media sakartvelos gazeti was published. The newspaper encompassed the decrees and orders of the central and local government, news of Russia and Georgia, novels, anecdotes, announcements (including the ones on selling serfs) and foreign news.

The origins of the censorship of the Georgian press can be traced back to 23 December 1837, when, based on the decree of the Russian Emperor, the Georgian administering authority was ordered to censor the books issued by the printing-house. The teachers of the Gymnasium of Tbilisi were appointed as censors.

On 18 December 1848, the Teaching District of Caucasus (Кавказский учебный округ) was established together with the Censorship Committee of Caucasus (Кавказский цензурный комитет). The committee was composed of a chairperson, who was also a deputy head of the Teaching district, and three censors.

The censorship committee was obliged to control not only local newspapers and books, but also foreign literature and if necessary, it should have detected and recalled them.

In 1855-1865, during the reforms carried out by Alexander II, great attention was payed to the freedom of press. The emergence of independent press in Georgia is related to these processes: in 1863, Ilia Chavchavadze published the journal sakartvelos moambe, which become the central body of tergdaleulebi. The journal did not last for too long and only 12 issues were published. The first Georgian-European standard newspaper was droeba led by Giorgi Eristavi. The newspaper existed until 1885 and significantly contributed to the spread of western ideas.

By the decree of 3 November 1874, the scope of the Censorship Committee of Caucasus was broadened and the provinces of North Caucasus, Stavropol, Tergi and Kuban were added to it. Besides Georgian, Armenian, Turkish, Arabic and Persian materials, the committee started censoring French, German, Italian and Polish press and literature.

After the reform of 1881, when the vicegerent of the Caucasus was replaced by the governor, the Censorship Committee became partly militarized body. In 1884, the unit of the inspector of Tbilisi printworks was added to it.

In 1881-188, publicist Luka Isarlov was appointed as a censor. His attitude toward Georgian writers was very strict. For instance, he extracted the best parts from Ilia’s achrdili, banned his poems musha; gazaphkhuli; elegia; ra vakete, ras vshvrebodit. He refused to publish Akaki’s poems and banned his public speeches.

By the end of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century, the wave of socialist movements and revolutions also approached Georgia. Many organizations and unions were created that fought for people’s rights and liberty. Some of these organizations gradually adopted criminal elements while some of them also became engaged in terrorist activities.

For gaining public support, it was necessary to spread the information about revolution quickly, which was followed by the establishment of illegal publishing houses. The Publishing House of Avlabari, which existed only for three years (1904-1906) until the gendarmes discovered and closed it, should be noted here. Later, Soviet historiography linked the establishment of this publishing house with Stalin, which, according to contemporary historians, is not true similarly to the other legends related to his figure. The publishing house was a room under a wooden house, in which revolutionaries managed to construct a printing machine. One can enter and exit the room through the tunnel from well. After the discovery, gendarmes destroyed the publishing house as well as the house on top of it.

The Publishing House of Avlabari was reopened on 20 August 1937. It was restored according to archival materials, oral stories and other sources. The exact copy of the house was built and an analogous typographic machine was placed under the ground. The Publishing House of Avlabari was a popular tourist destination in the Soviet times. [1] The long story about the publishing house is still being told at Stalin’s birth-house museum in Gori and a model of the building can also be found there.

The Publishing House of Avlabari today. Source: City.kvira.ge

Since 1906, the Censorship Committee has been named the Caucasian Committee on Press Affairs (Кавказскйи комитет по делам печати) and they became active fighters against the revolutionaries. Between 20 July 1914 – 27 April 1917, during the First World War, there was a temporary decree on military censorship and all kinds of printing activities were strictly controlled.

After the declaration of independence on 26 May 1918, the press censorship was abolished in the Republic of Georgia. The parties were granted freedom of speech and almost all of them managed to found their newspapers. The state and its particular institutions also published newspapers. For instance, the Ministry of Defense published the newspapers: kari, eri, mkhedari, sakhalkho gvardieli. The Ministry of Agriculture also had its own newspaper.

After some time, the situation regarding the freedom of press in the First Republic of Georgia worsened. The government periodically shut down the print media of the National Democratic Party: newspaper sakartvelo was shut down in 1919 and between May-August of 1920. Another newspaper of the National Democratic Party, klde was closed in Autumn 1919 [4] and its editor, Revaz Gabashvili was arrested. The reason for this was that the National Democrats criticized the presence of British army in Georgia, policy implemented in Abkhazia and the views expressed about the Patriarchate. Due to similar reasons, following the order of the Minister of Internal Affairs, the following newspapers were closed at different times: „Новости дня“ and „Тифлисская газета“.

During this period, the Bolsheviks were especially hostile to Georgia. They did not recognize the Democratic Republic of Georgia, supported separatist movements, organized rebellions and, therefore, their press faced challenges from the government. According to the treaty of 7 May 1920, Russia de jure recognized Georgia. One article of the peace treaty concerned the legalization of the Bolshevik press, after which their publications were not oppressed. Although the Ministry of Internal Affairs still managed to punish the Bolsheviks for the anti-state activities, granting the Bolsheviks the above-mentioned right posed significant risks.

The Last Page of the Treaty of 7 May 1920. Source: National Archives of Georgia

Since 1921, after the Soviet occupation, Georgia has forcibly become a part of Russia’s more “evil” empire. There were no free political elections, free press and public surveys in the Soviet Union. Therefore, the print media was ruled centrally by the Communist Party. During this period, it was impossible to read any opposing views. The newspapers were devoted to the glorification of the Soviet order and its leaders and the announcement of the messages “sent from above”.

In the Soviet Union, Main Directorate for Literature and Publishing – Glavlit (Главное управление по делам литературы и издательств – Главлит) controlled all kinds of print media centrally. This organization was created based on the decree of 6 June 1922. They had right to ban a publication and interfere in its dissemination if it:

- Agitated against the Soviet authority

- Revealed military secret of the republic

- Formed public opinion through spreading fake news

- Enhanced nationalist and religious fanaticism

- Had pornographic content

This body had been subordinated to the Ministry of Education before 1933 but then it was transferred to the Council of People’s Commissars. After that, before 1991, this organization had been transferred to the different bodies of the government but it is notable that, for all this time, it was the main censor of the country.

Glavlit was especially active in 1937-1938, during the repressions, when the repressions of more than million people should have been justified. In this period, the employees at the organization realized that any mistake would result in their repression. Therefore, not only the publications but also the copies approved and signed by the editor were under control. The officials of higher education were appointed as censors. During this period, there was a full-scale paranoia in the Soviet Union and people addressed strict self-censorship. A group of “volunteer censors” appeared, who notified Glavlit about the missed mistakes. [2]

However, it should be mentioned that neither Glavlit survived the mass cleansing. After they had done their “dark job” and discredited the repressed individuals, it was their turn. According to the report of 1939, 60% of the employees at the system had an experience of less than a year, 28% - less than 2 years, and only 12% - more than 3 years. Of course, they were cleansed through repressions and other means.

After the repressions wave, one of the central jobs of Glavlit became the retouching of old photos. The example of such retouching was Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov’s photo. In 1936-1938, Nikolai Yezhov was the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs and, through his hands, Stalin carried out the mass cleansing. Since 1939, Yezhov’s position had been lowering and on 4 February 1940, he was shot dead. In Stalin’s epoch, as a rule, people, who disappeared from photos, also disappeared from life.

Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov, photo before and after retouching. Source: www.history.com

Similar facts still appeared after the de-Stalinization. In 1953, after shooting Lavrentiy Beria dead, Soviet subscribers were sent a page of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia with instructions through post. They should have cut the page, which included an article about Beria, and stick the page they had received through post instead. [3]

Newspaper Communist 9 March 1953 (with Lavrntiy Beria’s removed photo). Source: IDFI’s archive

Another example is the 10 March 1956 and the following issues of the newspaper Communist. These issues included the information about the 5-9 1956 Tbilisi demonstrations that sacrificed the life of 21 people. The party decided that the information about these events should not have reached people.

Newspaper Communist, 10 March 1956. Source: https://www.idfi.ge/archive/

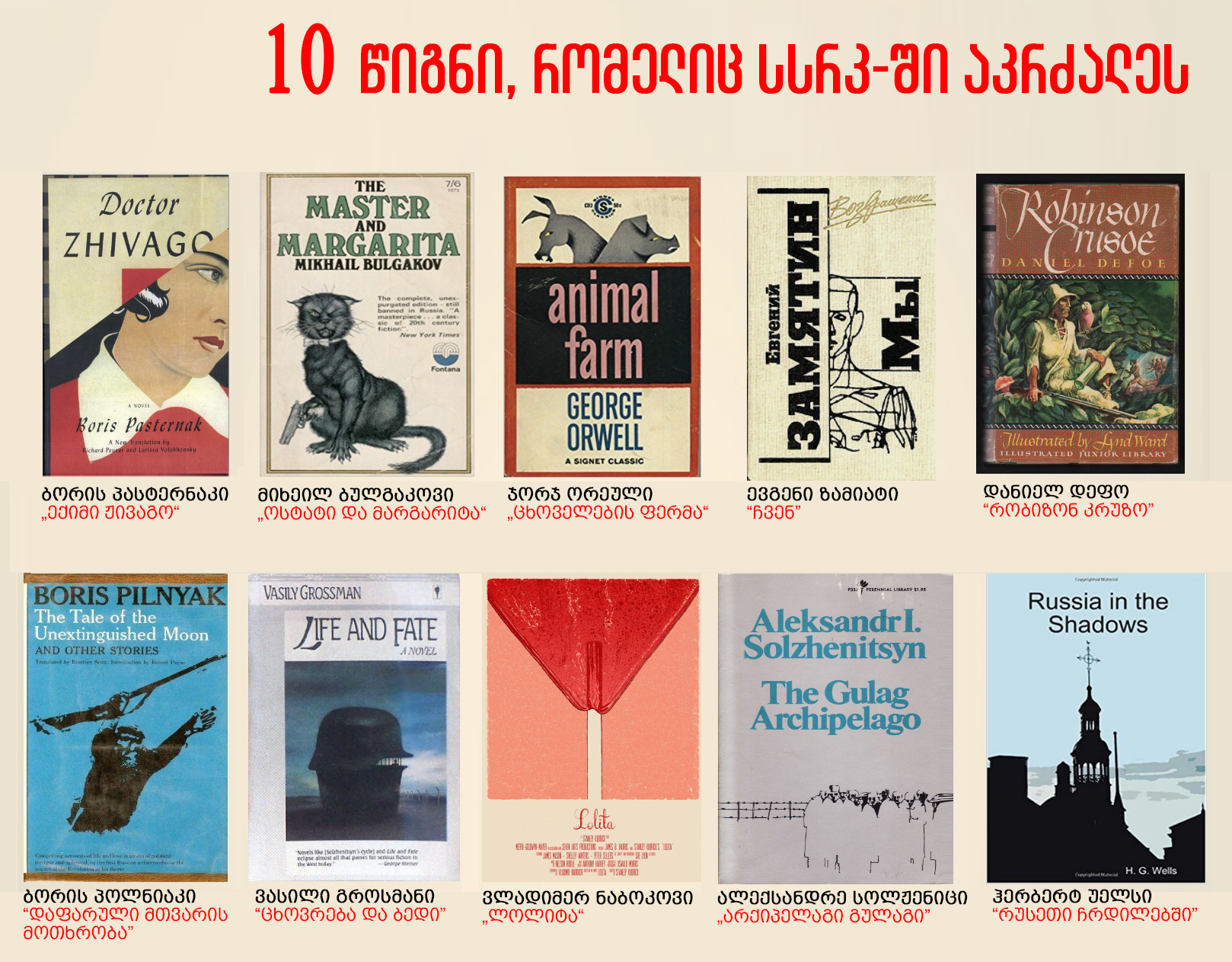

Glavlit managed to block the spread of the biggest literary works of that time. Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita was published only after 40 years following the author’s death. Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago was banned while, for this work, the author received the Nobel Prize. Hundreds of foreign literary works were banned, that, since 1970, have been spread in the Soviet Union through Samizdat. [4]

A short list of literary works banned in the Soviet Union. Source: Myth Detectors

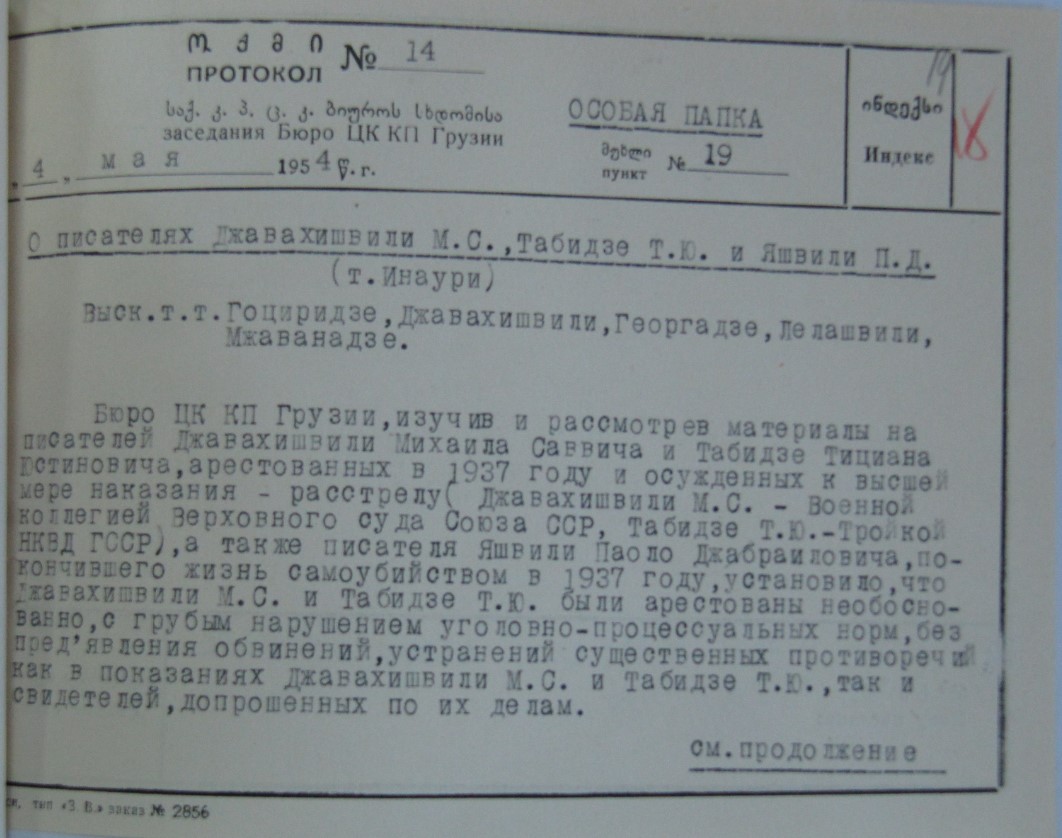

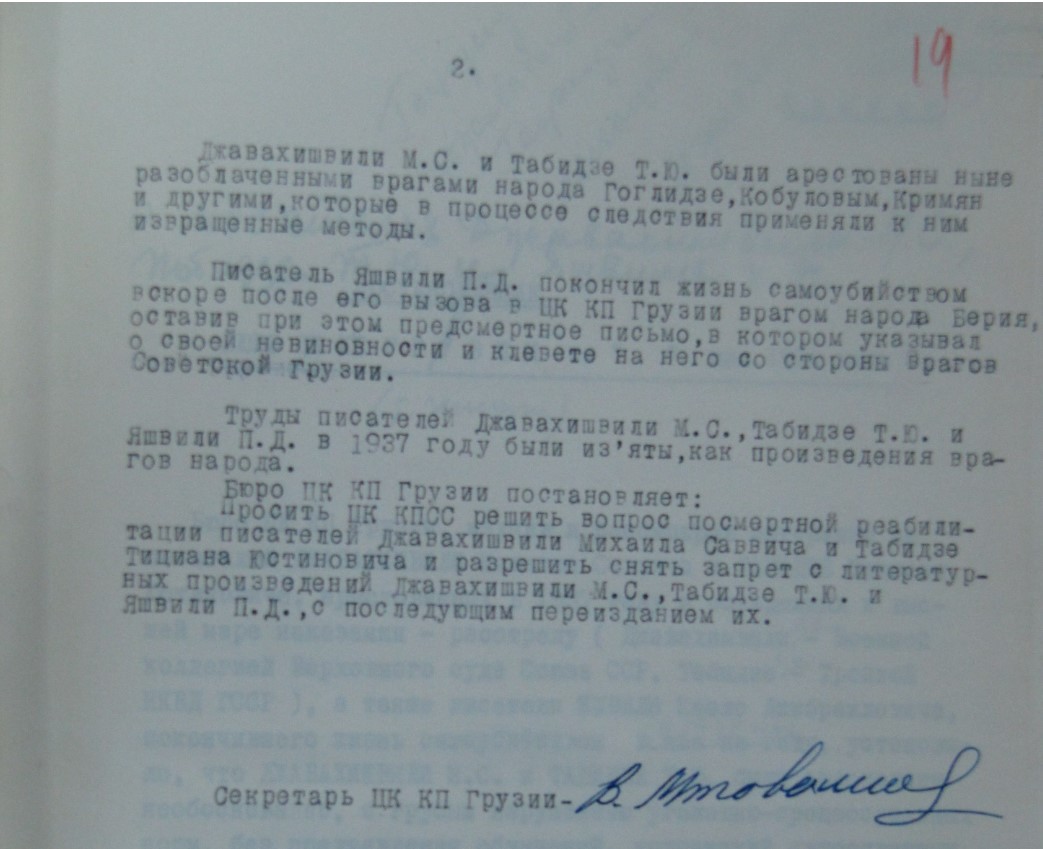

Similarly, the works of the repressed individuals and of those who were announced to be “the enemies of the people” were banned and recalled from libraries in Georgia. The examples of this are the works of Titsian Tabidze, Mikheil Javakhishvili and Paolo Iashvili. Only after Stalin’s death and Beria’s repression, when the rehabilitation of the victims of the 1937-1938 repressions started, their works became still accessible:

Source: MIA Archives of Georgia

There were different tendencies in the press of independent Georgia after the collapse of the Soviet Union. For instance, under Zviad Gamsakhurdia’s leadership, the law “On Press” was adopted, which banned any kind of censorship and ensured the spread on newspapers on the whole territory of the republic. However, the law enabled such interpretations that the newspapers were often accused of “spreading such facts that did not correspond to reality”. In May 1991, Gamsakhurdia forbid the opposition to use the governmental press. [5] Also, since 1991, Zviad Gamsakhurdia had been appointing the editors of governmental newspapers. In autumn, the Russian-language Novaya Gazeta (Новая Газета) (former Molodyezh’ Gruzii (Молодежь Грузии)) and akhalgazrda iverieli were closed. Journalists were also arrested. In 1991, after the Moscow Putsch, Russian newspapers were banned for one month. [6]

During the rule of Eduard Shevardnadze and Mikheil Saakashvili, there were not many examples of suppressing the freedom of print media, which was facilitated by the fact that the role of press as a medium in the society was decreasing. In this period, independent televisions appeared in Georgia that played an important role in political processes. The rude interference in the activities of independent media took place during both of these governments – first, in the case of Rustavi 2 and then in the case of TV Imedi.

Current Situation

In contemporary Georgia, in fact, the censorship on print media does not exist. Nowadays, there is a growing tendency of coordinated disinformation campaigns and hate speech in print media. There are a number of publications that use the above-mentioned methods on purpose. Through spreading the fake news and the usage of hate speech, they enhance the polarization in the society. Also, there is a problem of pressure on different media sources, their bribing for distorting information, using them for political objectives and the decrease of the level of their freedom. According to the research carried out by the international organization Reporters without Borders in 2020, considering the global index, Georgian press holds 60th place. The conclusion emphasizes the case of Adjara TV, which experiences the pressure from the representatives of particular party, as well as the case of Afgan Mukhtarli.

The Global Index of the Freedom of Press. Source: Reporters without Borders.

The freedom and impartiality of print media, accuracy of information and high standards are some of the most central principles of the democratic state. A significant progress was achieved in terms of fighting disinformation in December 2019 when Facebook deleted 418 pro-Governmental pages and accounts that were involved in “coordinated, inauthentic behavior”, which was expressed in the spread of anti-opposition and anti-Western narratives. Totally, $316,000 were spent on their advertisements.

___

[1] Newspaper Communist, 20 August 1937, №164.

[2] Александр Гужаловский, Главлитбел – инструмент информационного контроля белорусского общества (1922–1941 гг.), ActaSlavicaIaponica, Tomus 31, pp. 77‒104.

[3] "Soviet Encyclopedia Omits Beria's Name". The Times-News. December 2, 1953. p. 8.

[4]Samizdat (Самиздат) – a collective name of the underground publications in the Soviet Union. A group of people published handicraft, banned works and then spread them in the society.

[5] Steven Jones, Georgia: Political History after the Declaration of Independence, “Center of Social Studies”, Tbilisi, 2013, pp.92-93.

This material has been financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely with the creator. Sida does not necessarily share the expressed views and interpretations.