26 May 2020

The restoration of Georgia’s independence was preceded by the two important events: the restoration of autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church (12 March 1917) and the establishment of the Tbilisi State University (26 January 1918). As a historian, Otar Janelidze mentions that a famous Georgian scientist and public figure, Ivane Javakhishvili has significantly contributed to both of these glorious deeds. If he was just a participant in the fight for autocephaly, the establishment of the first national higher educational school was fully a result of his endeavor. [1]

The idea of Georgia’s independence originated earlier that 26 May 1918. Ivane Javakhishvili participated in these developments as a political actor.

In the 18-19th centuries, there was a revolutionary wave in Europe. The concepts of nation and nationalism, as we understand them today, were born within the frame of these revolutions, especially the French Revolution. The transfer of revolutionary wave from France to the other European states was followed by the distribution of different kinds of national ideas.

As Miroslav Hroch writes [2], for the formation of a national state, every nation goes through the three phases. At the first phase, smaller circles of intellectuals, who have access to education, begin the development of nationalist ideas and the creation of nationalist works. In the case of Georgia, the first phase started in the beginning of the 19th century when the romanticist writers (Aleksandre Chavchavadze, Grigol Orbeliani, Nikoloz Baratashvili) started the creation of nationalist works. At the second phase, the new generation of intellectuals start spreading their ideas and works through press. In Georgia, tergdaleulebi were leading this process. Final, third phase arrives when the whole nation mobilizes and a common national idea is formed. In Georgia, the third phase started in the beginning of the 20th century and finalized in the 1930s, Stalinist epoch. [3] The transition of the Georgian nation from the second to the third phase was accompanied by important historical events and not only writers and poets but also political figures and a historian, Ivane Javakhishvili, who created a national historical narrative for the Georgian nation in the period of national awakening, played an important role in this process.

By the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, Russian Emperor, Nicholas II’s policy in the center and periphery became relatively mild and the exchange of ideas became more active. The idea of self-determination and independence, which was very popular at that time, also spread in Georgia. The weakness of political problems of the Emperor were already visible but the instability intensified as a result of the 1905 revolution and the defeat in the adventuristic war started by Russia against Japan. The First World War and revolutions resulted in the collapse of the Russian Empire. [4]

In the 1890s and 1900s, Tsarism actively oppressed Ivane Javakhishvili, did not allow him to publish his works and there were several cases of detention. Since the 1910s, spying on Javakhishvili continued but the attitude toward him became much more loyal. Ivane Javakhishvili was often invited to read lectures in Tbilisi and he devoted his speeches to the problematic issues of the history of Georgia.

Ivane Javakhishvili’s research and public lectures on patriotic thematic not only facilitated Georgians’ interest in their own past but also supported the liberation from Tsarism and political independence. Mikhako Tsereteli wrote in his letter to Javakhishvili: “The publication of your monographs and books is a great deed not only for scientists but for our incarnation. This is the best propaganda of the Georgian idea. I know this based on my observation and experience… When I was in Tbilisi, I saw how your lectures made many unbeliever and ignorant people believe in Georgia”. [5]

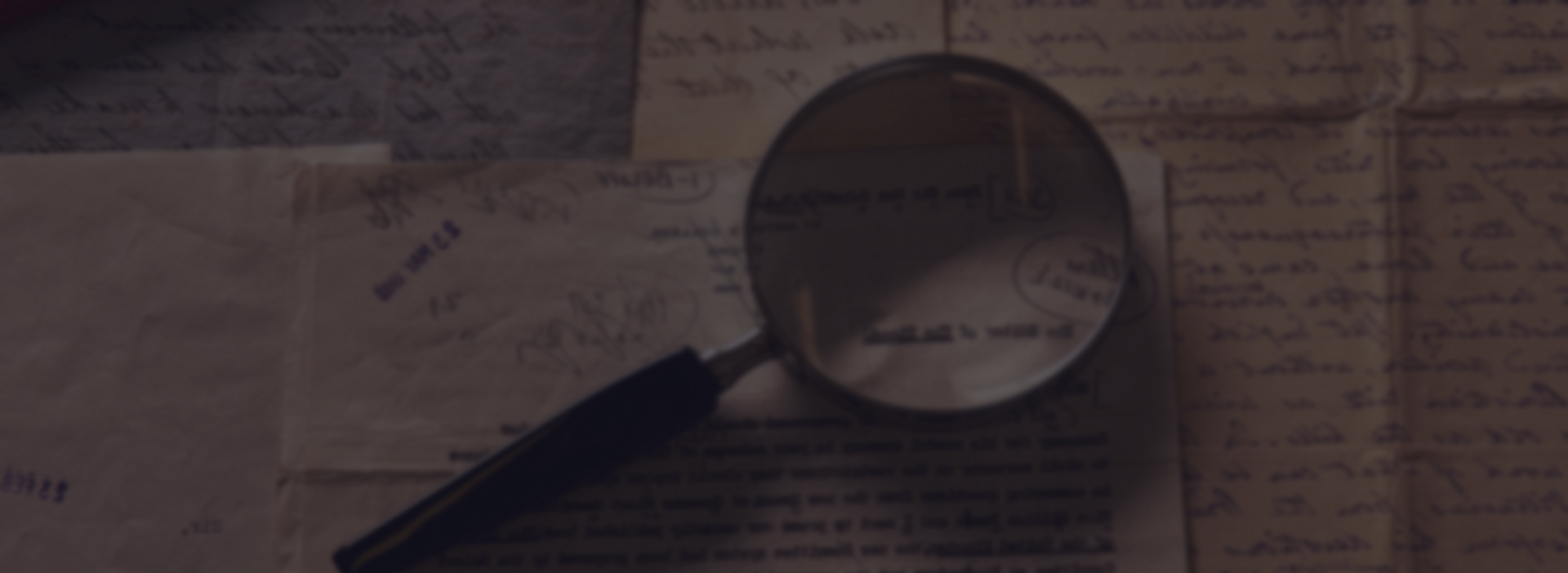

For instance, we can refer to the Head of Historical and Ethnographic Society, Ekvtime Takaishvili’s simple request to the Police Chief of Tbilisi about conducting Assistant Professor of the University of Petersburg, Ivane Javakhishvili’s lecture. It’s notable that, under the Russian Empire, the topic of the lecture was “The Economic Structure and Conditions of Georgia in XVII-XVIII Centuries” and there is not a single word about saving Georgia from Persians by Russia in the abstract, which was an ideological necessity at that time.

Source: National Archives of Georgia, Central Historical Archive, fond 17, opis 1, delo 8036.

The intensification of Ivane Javakhishvili’s political activities in Georgia as well as abroad took place in parallel with the First World War and the strengthening of the idea of independence.

The intelligence note created in December 1916, which reveals this participation, is preserved in the National Archives of Georgia. In addition, there are some interesting notices showing the distribution of idea, on the one hand, and the importance of the support of European countries to Georgia, on the other hand:

Special Secret

To His Majesty, Assistant of the Vicegerent on the Social Issues of the Caucasus / at the Special Department/

15 December 1916/ received on 17 December 1916

Report

After granting autonomy to Poland, the minds of a significant number of Georgians have been occupied by the issue of Georgia’s independence. This issue is being discussed in press as well as private talks, where the Social-Federalists and Social-Democrats are present. Prince Grigol Diasamidze is their leader. He does not belong to any party, he just organizes these meetings.

On 20 November, the Catholics living in Tbilisi, on the initiative of above-mentioned Diasamidze, organized a funeral rite for the dead Polish writer, Sienkiewicz. During the funeral, the Georgians congratulated the Polish people on their declaration of independence and the Polish people expressed their hope that Georgia would receive autonomy in the nearest future. The organizer of the funeral made a speech about the Polish autonomy and expressed his hope that Georgia would achieve autonomy as well.

During the funeral, the Polish people performed their national anthem “Poland Is Not Yet Lost”…

There are some notices that the Georgians living in Petrograd are also concerned with the issue of Georgia’s autonomy. Javakhov (author: Javakhishvili), living there, sent a letter to the Head of the Society for the Spread of Literacy among Georgians, Samson Pirtskhalava, in which he says that the new Minister of Foreign Affairs of Germany, Zimmermann is well-aware of the Georgian issue, is interested in it and has promised to emphasize this issue during the peace talks.

Javakhov had allegedly incognito visit to Stockholm where he held talks about Georgia with the Ambassador of Germany. The content of these talks are being kept secret. Javakhov – a historian, ardent supporter of autonomy and federalism, basis his conclusions on historical documents.

I am honored to report about the above-mentioned to Your Majesty and inform you that the spying is being carried out on the above-mentioned meeting.

Colonel: Pastriulin. [6]

There is no further information about this notice acquired through spying by the gendarmerie. Neither Javakhishvili remembers this fact in his later works. However, it should be mentioned that travelling from Petrograd to Stockholm was not difficult at that time. [7] Moreover, the Embassy of Germany in the capital of Sweden was the center of propaganda activities aimed against the Russian Empire. [8]

On 20 May 1917, in the newspaper “kartuli gazeti”, issued in Berlin, a notice was published, according to which the Georgians living in Petersburg met and unequivocally adopted a resolution on the restoration of Georgia’s political rights as an autonomy. For notifying the government about the resolution, attracting press and society and establishing close ties with the representatives of different nations, a committee was elected, which included: assistant professors – Iv. Javakhishvili, Iv. Kipshidze and Nutsubidze, N. Gelovani, lawyer – G.Sidamon-Eristavi, Z. Avalishvili, A. Cherkezisvili. [9]

In this period, even the most optimistic national powers would not predict the full restoration of Georgia’s independence and, for this, their majority required a broad autonomy. Everything changed after the First World War and the internal revolutions in Russia, after which Georgia managed to declare independence.

Ivane Javakhishvili was actively involved in the activities of the First Republic of Georgia after the declaration of independence, even though he was not elected as a member of the Constituent Assembly. As a historian and scientist, he participated in the decision-making process on important state issues: creation of the national flag and coat of arms, restoration of the Georgian toponymy, formation of the national narrative and creation of educational program for schools. He was a member of the Constitutional Commission and was in charge of the most problematic issue – the issue of state borders. [10]

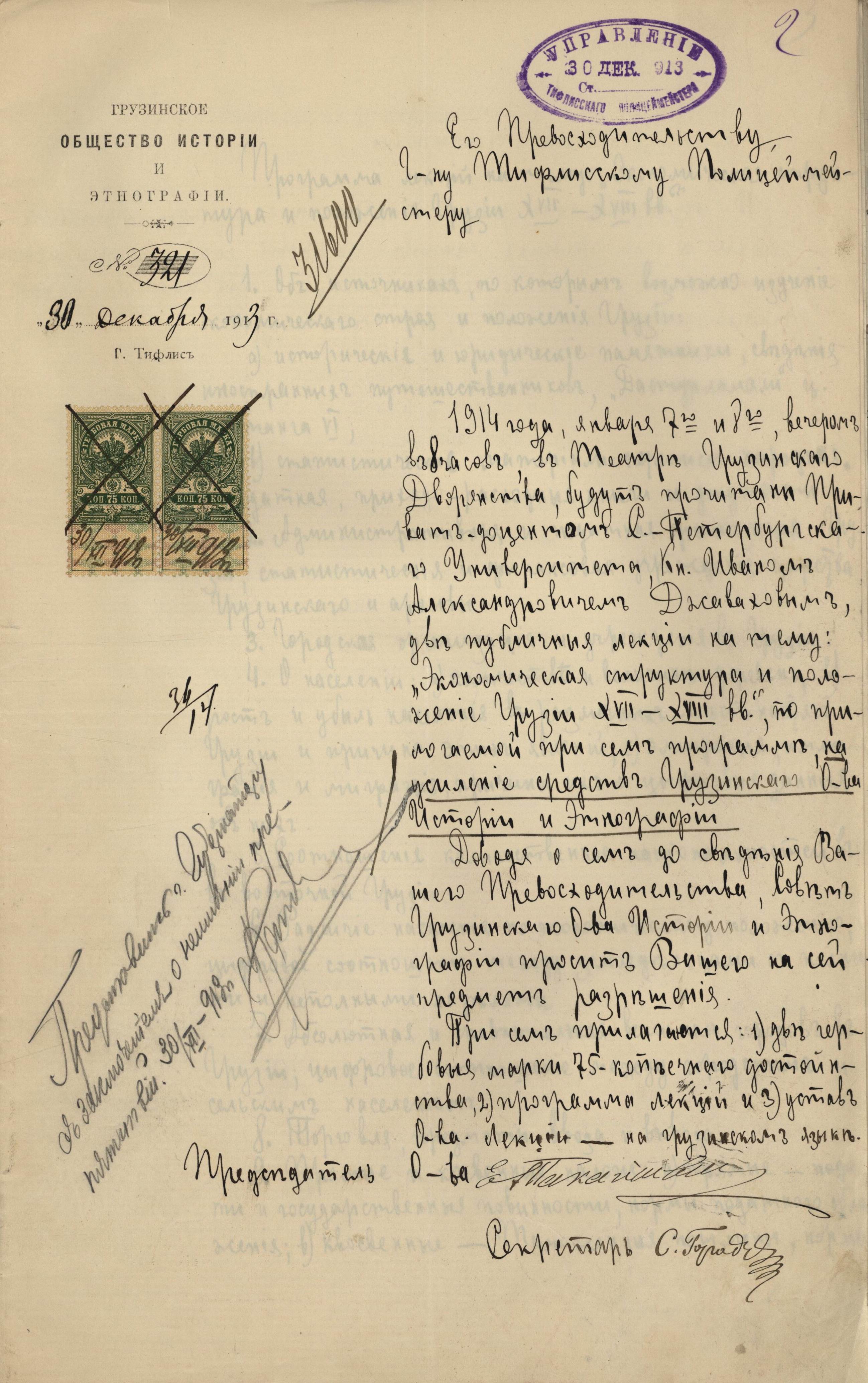

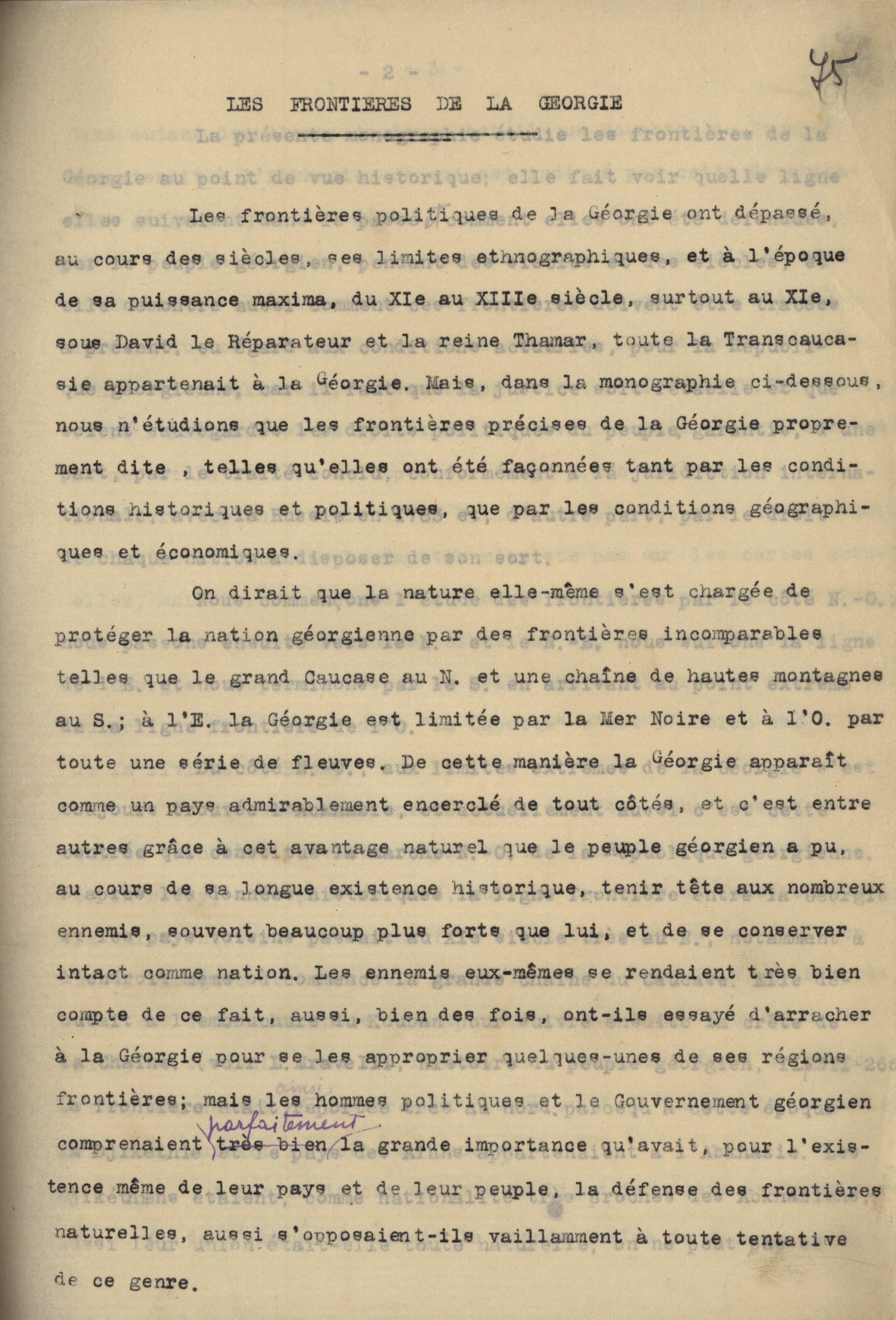

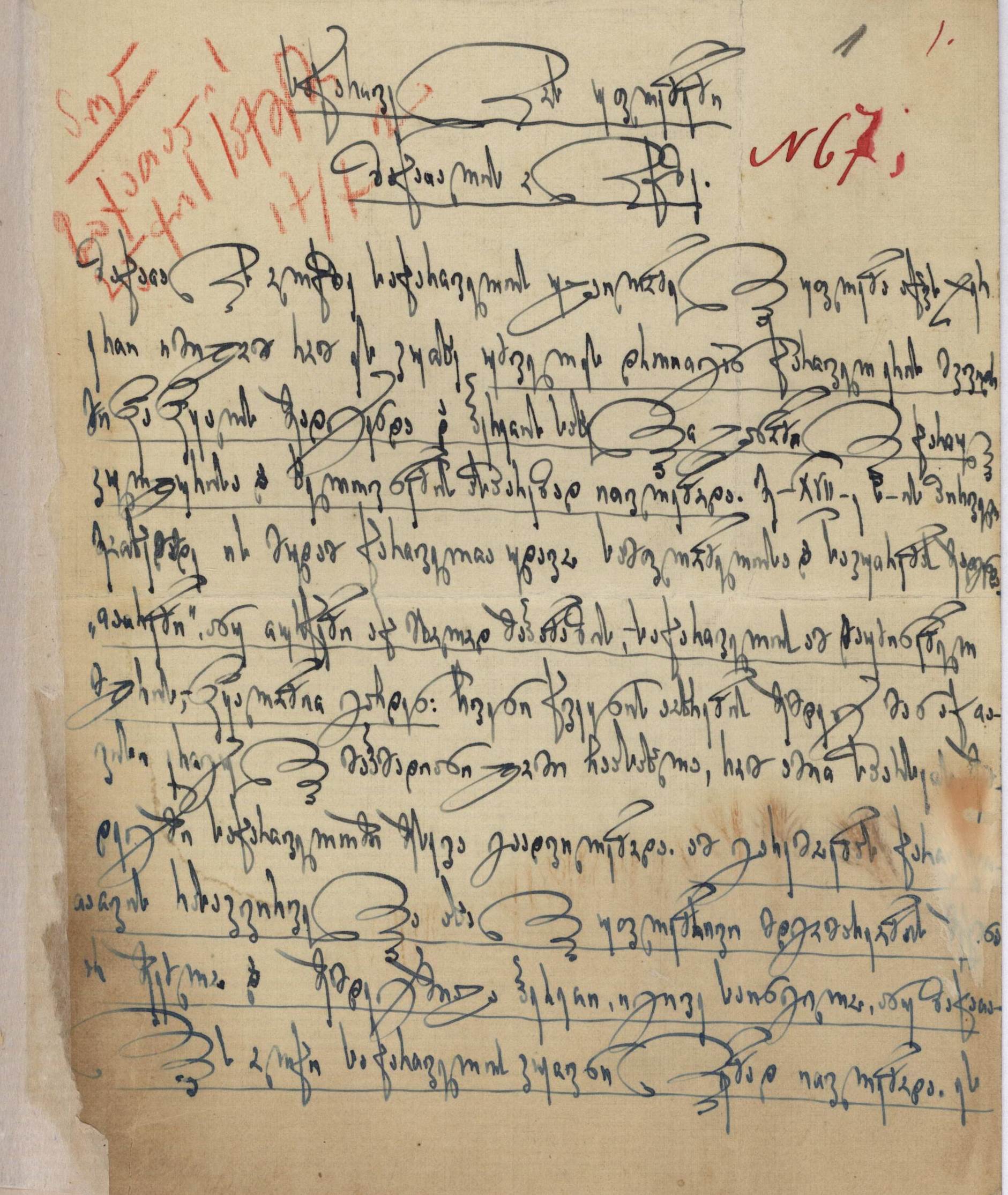

Ivane Javakhishvilis’s work: The Borders of Georgia according to History and Contemporary point of View, handwriting (first page) and the French translation of the documented prepared for the international society. 14 October 1920. Source: National Archives of Georgia, Central Historical Archive, fond 1864, opis 2, item 273.

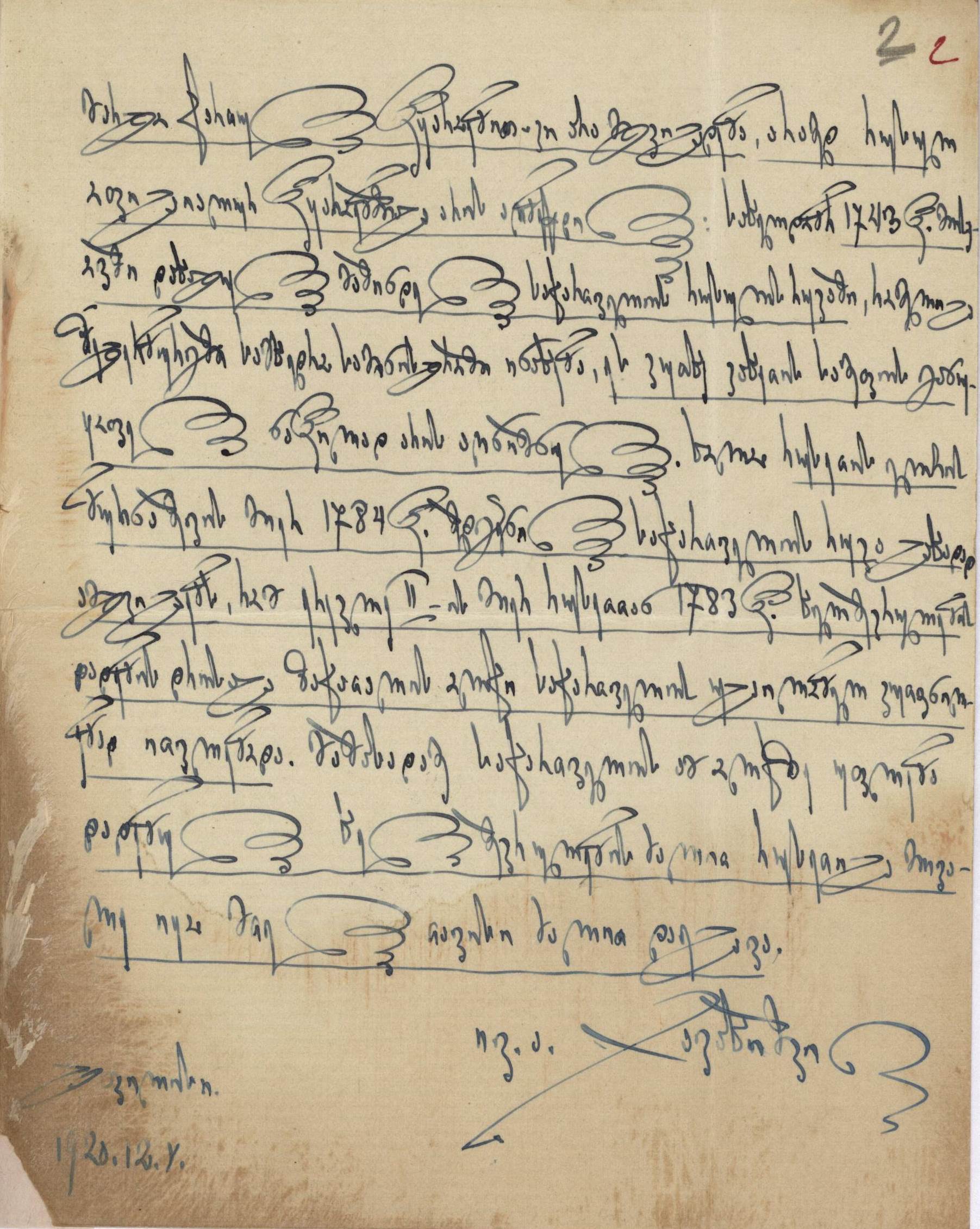

Ivane Javakhishvili’s handwriting: Georgia’s Legal Rights on Zakartala District, handwriting. 12 May 1920. Source: National Archives of Georgia, Central Historical Archive, fond 1864, opis 2, item 274.

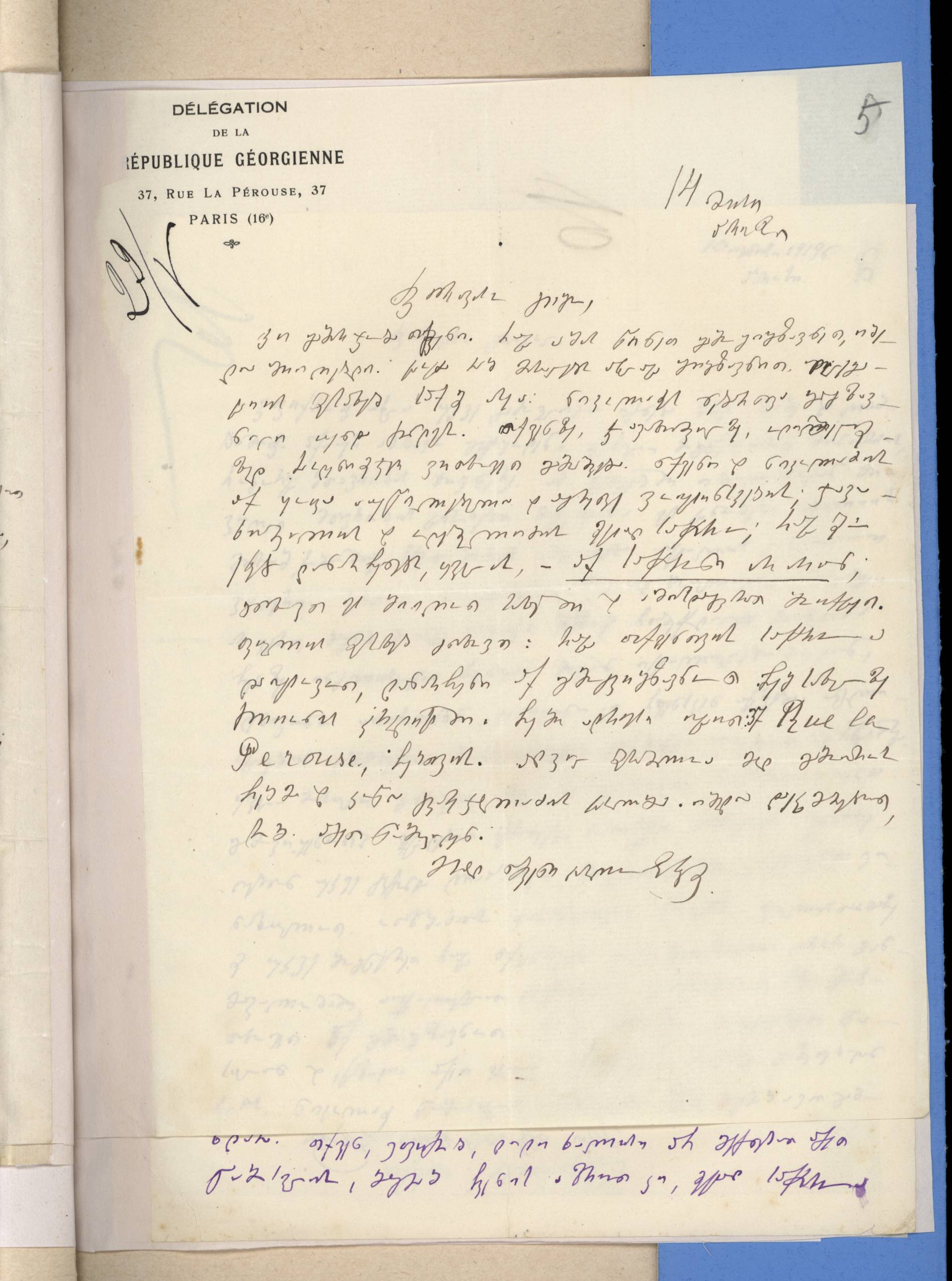

Ivane Javakhishvili was elected as a member of the Georgian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference. The Conference started on 18 January 1919 and it was focused on the creation of the new international order after the First World War. The issue of the self-determination of small nations was raised on the Conference, which gave a historical opportunity to Georgia to enhance its independence and gain international recognition. [11] The decision of the Social-Democratic government of the First Republic of Georgia to send educated and experienced people such as Niko Nikoladze and Zurab Avalishvili (National Democrats), Ivane Javakhishvili (non-party member) and others to the Conference and not to focus on narrow party interests can be considered as a progressive approach. The chairman of the Parliament of Georgia and the Paris Peace Conference, Karlo Chkheidze wrote to one of the leaders of the Socialist-Federalist Party, Grigol Rtskhiladze: “A confirmation should have already been sent to Nikoladze. We also asked to let you, Javakhishvili and Odishelidze to come with us. Your, Javakhishvili and Odishelidze’s presence is very important here, others are not needed”.

Karlo Chkheidze’s letter from Paris to Grigol Rtskhiladze on establishing a diplomatic mission (14 May 1919). Source: national Archives of Georgia, Central Historical Archive, fond 2115, opis 1, item 90.

When the end of the First Republic was near as the Russian armies had already invaded Georgia, on behalf of the professors of the university, Ivane Javakhishvili and Akaki Shanidze sent a letter to the Defense Committee of the Constituent Assembly, in which they expressed their readiness to contribute their knowledge and physical abilities, as needed, to the defense of their homeland.

Source: National Archives of Georgia, Central Archive of Contemporary History, fond 471, opis 1. item 110, p. 13.

Based on all of the above-said, the orchestrated oppressions against the great scientist is not surprising. In 1926, he was dismissed from the position of the Rector of the Tbilisi State University and in the 1930s, a fight against him as a scientist started. [12] Finally, Ivane Javakhishvili was restored to the academic position at the university because, presumably, in the highest echelons, competent scientists were needed for broadening the research on Georgia’s past and the creation of new works. [13] On the other hand, Ivane Javakhishvili was also influenced by the political conjuncture and it can be argued that he became adrift, which is proved by the works such as “Where Does the Surname of the Leader of the Peoples Originate from” (Откуда пошла фамилия вождя народов) and others created by him.

Unfortunately, all of the above-mentioned sacrificed the life of a 64-year-old man untimely...

___

[1] Otar Janelidze, Historical Essays on the First Republic of Georgia, “National Library of the Parliament of Georgia”, Tbilisi, 2018, p. 129

[2] Miroslav Hroch, Comparative Studies in Modern European History: Nation, Nationalism, Social Change, Aldershot; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Variorum, 2007, pp. 95-96.

[3] Ronald Grigor Suny, The Making of the Georgian Nation, London: Tauris, 1988.

[4] Verner, A., The Crisis of Russian Autocracy: Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990); Lieven, Dominic, Nicholas II. Twilight of the Empire, (New York, 1996).

[5] Otar Janelidze, Ivane Javakhishvili, Tbilisi, 1996, p. 4.

[6] National Archives of Georgia, Central Historical Archive, Fond 13, d. 27, case 4425, pp. 11-12.

[7] Otar Janelidze, Ivane Javakhishvili, Tbilisi, 1996, p. 13.

[8] S.Zaterberg, Die liga der Fremdvolker Russlands 191-1918. Ein Beitrag zu Deutschlands antirussianischen Popagandandakrieg unter den Fremdviolkern Russlands in ersten Weltkrieg. Helsink, 1978. ss. 43-44.

[9] “kartuli gazeti”, 20 May 1917.

[10] See: Otar Janelidze, Historical Essays on the First Republic of Georgia, “National Library of the Parliament of Georgia”, Tbilisi, 2018.

[11] See: Margaret Macmillan, Paris 1919, New Your, 2002.

[12] See: Megi Kartsivadze, Anton Vacharadze, History Politics in the Soviet Union and Prof. Ivane Javakhishvili's Fate. https://www.idfi.ge/archive/index.php?cat=read_topic&topic=153&lang=ka

[13] For Stalin, it was important to represent himself as a son of a great culture. As the Russian authors of that period mentioned, the Russian chauvinist elites of the 1930s observed national cultures as an exotic. See: Е. Гальперина, "Формы проявления великодержавного шовинизма в литературоведении и критике", РАПП, № 5-6 (1931): стр. 47.