12 March 2025

Authors: Giorgi Kldiashvili, Levan Avalishvili

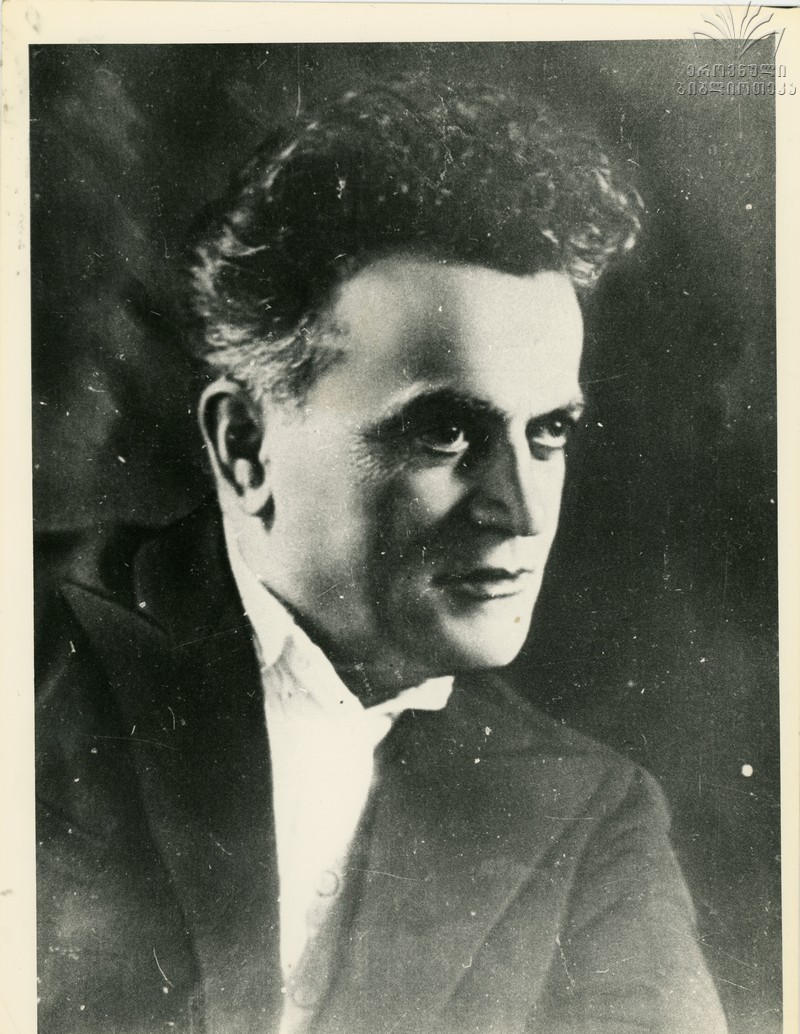

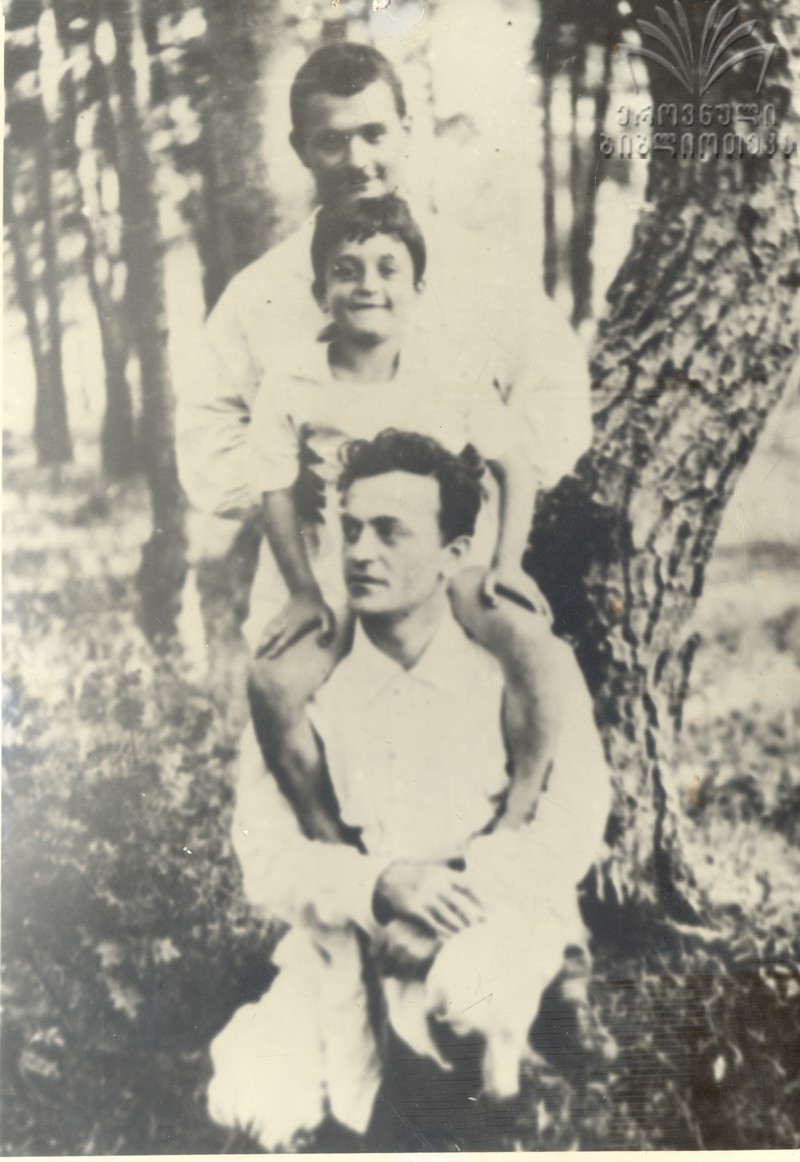

The 1930s remain one of the most important and interesting periods of Georgian history, with many pages still unstudied. One such blank page that we can now begin to fill concerns the persecution of Rustaveli Theater director Aleksandre (Sandro) Akhmeteli, along with the theater’s entire troupe. The authors have found a file regarding this case in the Presidential Archive of Georgia (formerly the Party Archive of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia). The documents in this file contain numerous interesting materials that concern not only this specific case but also reflect, in general, an epoch characterized by very painful and difficult events for our country.

On February 11, 1956, the Military Board of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union vindicated a number of "repressed" persons, including Sandro Akhmeteli, Artistic Director of Rustaveli Theater, and theater employees Platon Korisheli, Elguja Lortkipanidze, Gia Kantaria, Ivane Laghidze, Tamar Tsulukidze-Akhmeteli, Bezhuzha Shavishvili, and Nino Gviniashvili. These people had previously been considered guilty by the Military Board. In particular, Sandro Akhmeteli was accused of espionage for the British intelligence services, membership in a Trotsky-Zinoviev counterrevolutionary organization, and "wrecking" in the artistic sphere. He was accused of establishing seditious military groups in Baku, Grozny, Sokhumi, Stalinir (Tskhinvali), and other regions of Georgia with the support of national theater administrations in the other republics and of personally recruiting 35 persons as organizers of these groups. Furthermore, Akhmeteli was not only accused of establishing the above-mentioned terrorist organization but also of plotting to assassinate Lavrenty Beria and Joseph Stalin with the assistance of this organization.[i]

On June 28, 1937, Aleksandre Akhmeteli, Platon Korisheli, Elguja Lortkipanidze, Gia Kantaria, and Ivane Laghidze were sentenced to death with property confiscation according to Article 58 of the Penal Code of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Georgia. Tamar Tsulukidze-Akhmeteli, Bezhuzha Shavishvili, and Nino Gviniashvili received ten-year sentences. From 1922 to 1926, Aleksandre Akhmeteli had worked as a producer at the Rustaveli Theater. After that, he held the position of Chief Producer and then Artistic Director until his dismissal in 1935. Following his dismissal, Akhmeteli moved to the Green Theater in Moscow.

The investigation conducted by the rehabilitation commission showed that Akhmeteli was arrested on November 19, 1936, in Moscow and then transported to Tbilisi. Several questions arise concerning Akhmeteli's arrest: the decision to arrest him was issued on December 5, and he was informed of this order on December 7, eighteen days after his actual arrest. The arrest was conducted without a prosecutor’s order, and a prosecutor did not appear or take part in the preliminary investigation or the court hearing.[ii]

Akhmeteli was detained for seven months (November 1936–July 1937). The case file materials show that for his first three months of detention, he denied all charges, but afterward, under physical and psychological duress, he not only admitted his guilt but also "named" more than 200 persons who were supposedly taking part in counterrevolutionary activity with him. Many of those named were well-known political leaders, deputies, and writers, including Budu Mdivani, Giorgi Kurulov, Mikheil Javakhishvili, Shalva Dadiani, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, Paolo Iashvili, Titsian Tabidze, and the entire Rustaveli Theater troupe. It must be concluded that Akhmeteli’s case was being used not only against him but also against Georgian intellectuals and the political elite of the entire country.[iii]

The minutes of the court hearings clearly show that court hearings for each of the accused lasted only several minutes. They were not properly interviewed in connection with the accusations against them, and contradictions between evidence from the preliminary investigations and testimony given during the court hearings were ignored. Furthermore, the court was not even interested in the fact that the accused recanted their confessions. For example, Tamar Tsulukidze, Akhmeteli’s wife, denied her confession given during the preliminary investigation and declared at the court hearing that she "feels guilty herself but does not know what for particularly." Korisheli, Lortkipanidze, Shavishvili, and Gviniashvili also declared that they did not recognize their guilt, although later they partly "confessed."

It should be emphasized that some of the witnesses in this case were later arrested and executed (L. Gasviani, A. Giorgadze, and I. Zurabishvili, among others). Those who survived the repressions vigorously denied their confessions given in 1936–37 during the rehabilitation procedures, declaring that NKVD investigators usually obtained confessions through torture and fabricated evidence (for example, A. Davitashvili, A. Kavtaradze, and A. Vasadze).[iv]

From this point of view, testimony from two witnesses is particularly important: Kvlividze, who was also arrested and placed in the same cell with Akhmeteli, later stated that the famous producer was brought to the breaking point and forced to confess through ceaseless torture. According to Kvlividze, Akhmeteli regretted that he did not "confess" all of the fabrications sooner to end the investigation and the torture. Akhmeteli also realized that the person behind the case against him was Lavrenty Beria himself, with whom he had a poor relationship.[v]

Another witness, Atashian, who introduced himself as a former employee of the NKVD, admitted that Shekotikhin, the investigator handling the Rustaveli Theater case together with Mkheidze and Podolskaia, often used especially brutal methods of coercion. The same was admitted by Akhmeteli’s wife and by Nino Gviniashvili, who survived until the start of the rehabilitation process.

Incidentally, two of the investigators of the case, NKVD officials Mkheidze and Shekotikhin, were arrested later the same year, in 1937, and both were sentenced to death. Podolskaia was arrested because her husband, Shutov, was convicted of conspiracy against the Soviet Union. Later, Podolskaia’s case was suspended, but her whereabouts remained unknown.[vi]

The documents in the file clearly show all of the actual motives that formed the basis for the Akhmeteli case. The materials demonstrate that the OGPU and NKVD had been conducting surveillance on Sandro Akhmeteli and other actors of the Rustaveli Theater since 1928. Lavrenty Beria, as head of the Georgian OGPU, personally supervised the surveillance. In 1930, on Beria’s order, the Rustaveli Theater’s overseas tour was canceled.[vii]

The surveillance continued up until Akhmeteli’s arrest. The case file also provides descriptions of the disagreements between Akhmeteli and Beria. The first point of conflict was Akhmeteli’s hot temper: he simply did not want to obey Beria’s orders and bend to his will. According to some sources, Akhmeteli spoke about Beria offhandedly in conversations with friends. Based on statements from Konstantine Gamsakhurdia and Jikia, during a private conversation in 1935 between Beria and Akhmeteli, the latter addressed Beria roughly, using very vulgar words.[viii]

According to Kacharava’s evidence, he (Kacharava) overheard a conversation between Dekanozov and Beria in the spring of 1935 and heard Beria angrily referring to the “impudent” Akhmeteli, who had hung a photo taken with Stalin in Rustaveli Theater without his permission. Of course, Beria took advantage of a confrontation between the Artistic Director and two of the theater’s leading actors, Akaki Khorava and Akaki Vasadze, and tried his best to exacerbate the quarrel between the artists and their supporters. This story ended with the demotion of Akaki Vasadze by Akhmeteli, and Khorava was sacked from the theater. Akhmeteli did not obey a direct order from Beria to restore Khorava and Vasadze to their positions, and with this, Beria’s patience ran out. That same year, Akhmeteli was dismissed from his position, and a year later, he was accused of espionage and many other fabricated charges.

The file also reveals one very important fact: it shows that Akaki Vasadze was a key witness in the Akhmeteli case. It was Vasadze’s testimony that became the basis for the formulation of the central accusations. Besides Akhmeteli, Vasadze alleged that many famous persons were directly involved in “counter-revolutionary” activity. Particular focus was placed on well-known political figures, writers, and artists, including writers and poets such as Mikheil Javakhishvili, Titsian Tabidze, Paolo Iashvili, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, Dadiani, and Shanshiashvili; artists such as Khorava, Sagaradze, Kaparidze, and Dito Shevardnadze; and political officials of the period such as Budu Mdivani, Mamia Orakhelashvili, L. Gogoberidze, P. Orjonikidze, and Lidia Gasviani.[ix]

According to Vasadze’s statement, Sandro Akhmeteli purposefully conducted counter-revolutionary sabotage at the theater, had contacts with Georgian émigrés abroad and regularly received financial support from them, staged anti-Soviet theatrical performances, maintained close relations with the administrations of theaters from different Soviet republics (especially in Ukraine), focused on nationalistic themes together with members of these theater administrations, established and led a seditious group at the theater, supported the incitement of an antisocial spirit among students, always emphasized nationalist themes in his private conversations, and, because of his pro-fascist spirit, conspired with other accomplices to assassinate Lavrenty Beria and other party leaders.[x]

Vasadze was summoned for interrogation three times, and his list of “counter-revolutionary organizations” was repeatedly updated with new names. As a result, six more people were sacrificed to the meat grinder, among them Petre Otskheli, Vakhtang and Ivane Abashidze, and Aleksandre Tarkhnishvili.[xi]

Vasadze’s testimony provides an opportunity to learn about how events unfolded at Rustaveli Theater during those years and to become acquainted with the personal details of the theater staff, as well as the confrontations among them and the key role played by Beria—the First Secretary of the Central Committee—in these disputes.

Akaki Vasadze was interviewed again in connection with the Akhmeteli case during the rehabilitation process. At that time, he denied all the accusations leveled against the Artistic Director of Rustaveli Theater that were based on his statements. He also denied the authenticity of the minutes of his statements. Forensic specialists had to prove the authenticity of his signature on the minutes, and Vasadze eventually confessed that the minutes were not forged, though he could not explain how his signatures appeared on the documents.[xii]

The only explanation Vasadze could offer was that Beria had psychologically manipulated him, and the investigators took advantage of his condition, successfully substituting the minutes at the last moment for him to sign.[xiii]

Despite Vasadze’s statement, dated April 14/16, 1937, and his testimony on a number of facts concerning “counter-revolutionary activity” by Sandro Akhmeteli and his troupe, on April 20, 1955, in a statement given to the rehabilitation commission, Vasadze said that he had no information about any counter-revolutionary activity conducted by Akhmeteli.[xiv]

On July 6, 1955, Judge Advocate Colonel Tsumarov presented his conclusion on Sandro Akhmeteli and the Rustaveli Theater personnel who had been persecuted as a result of the Akhmeteli case. The conclusion stated: “I believe that the judgment imposed on all persons involved should be considered invalid, and the case closed due to the absence of a crime.”

The documents in Akhmeteli’s case file thoroughly present the entire pathos of the 1930s. His case provides a clear understanding of the events of that era, describing various aspects of social life, illustrating how ambitions and interests led to intrigues, personal confrontations, and the loss of hundreds of lives. Most importantly, it reveals the brutal mechanisms of the Soviet state security organs, detailing how evidence was obtained under pressure, statements were fabricated, and individuals were physically liquidated. The case of Sandro Akhmeteli and his troupe remains one of the most significant and notable files preserved in the Archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia.

[i] Party Archive of the Central Committee of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia – Today officially referred to as the Presidential Archive of Georgia (Tartarkhiv TsK KPG), f. 14, o. 31, d. 247, p. 3.

[ii] Tartarkhiv TsK KPG, f. 14, o. 31, d . 247, p. 4-5.

[iii] Ibidem – p. 4-5

[iv] Ibid., p. 6

[v] Ibid., p. 14.

[vi] Archive of the III section of the Archive Administration of the MoIA – f.#14; file #247; p. 14

[vii] Ibid., p. 13.

[viii] Ibid., p. 12.

[ix] Ibid., p. 7.

[x] Ibid.,pp. 18-24., 25-35., 36-38.

[xi] Ibid., p. 10.

[xii] Ibid., p. 39-41.

[xiii] Ibid., p. 49-50.

[xiv] Ibid., p. 14.